ANDREW SUNSHINE

John Hancock's John Hancock: On the Signature, of All Things

A

In 2001, when my son Gabriel, then six years old, applied for his first passport, he could write his name, but he couldn’t sign it. At least, he had not had occasion to do so until then. His spelling out of his name on that document became (for the time being) his signature.

Six years later, when he renewed his passport, Gabe produced something that looked more like a signature. It was a kind of cursive monogram of his initials. [1] What was going through his head when he devised his logo?

B

When does one go from knowing how to spell one’s name to signing one’s name? Where is the threshold one crosses the first time one signs one’s name? How does one sign one’s name for the first time? What made Gabriel’s writing of his name on his first passport a signature? What does the signature inscribe within?

Is the difference between a child’s spelling of his name and his first signature a material one? I think it is primarily—meaning: originally—a linguistic distinction, but one that is bound up with social and psychological development. Which is to say, the difference is functional; it relates to social roles and social being. Signing one’s name is a deictic activity, where mere spelling is not (or is only secondarily so): One signs one’s own name; one does not sign someone else’s name. Or: one spells in the third person; one signs in the first. But where does the signature reside? In the written corpus? In the act of signing? In the intention inferred by its readers? And yet, if not from the start, still inevitably, the signature develops in a singular direction; it diverges from spelling.

C

Over the years, my own signature has undergone several transformations, but the most drastic of these occurred, I think, before I reached the age of twenty. (More recent changes are consequences of having to sign a great many letters often all at one sitting at my office desk and also of age—sometimes my hand aches.) But the two principal signatures I devised in childhood were products of observation, emulation, and deliberation.

My first major signature was a jumbled ball of letters furiously overlapping to such an extent as to be entirely illegible and perhaps hard to distinguish from a fly come to rest momentarily on the page. Its source was an astute observation: signatures aren’t necessarily legible; what’s most important is that they be recognizable or identifiable and distinct. Perhaps I had also noticed: importance seems to go hand in hand with illegibility. An illegible signature was inscrutable, indifferent to its readers. What could be cooler?

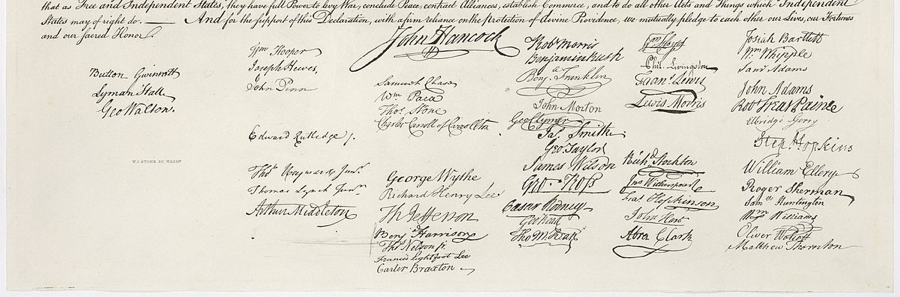

My next signature was the result of a search for something other than the aura of impenetrability: by this point (at the age of twelve, a year or two after having concocted the signature just described) I had had the opportunity to see our nation’s founding document, the Declaration of Independence, or at least a replica on a piece of ersatz parchment paper someone had purchased for me in a souvenir shop at a site of historical significance (not necessarily Philadelphia). It is a veritable menagerie of signatures.

Different though the signatures are one from another, they still bear some affinities or family resemblances: they bear the signature of their times, as it were. Many of them are festooned with flourishes which sometimes tie the Christian name to the surname and at other times simply tie up the name with a pretty bow (most notably, prominently John Hancock). You rarely saw such touches in the adult signatures of my own day, but why not? Why not integrate an elegant gesture or two into my own signature? So, I did.

ASunshine

A flourish started from the end of the (final) e and looped leftward back over the h and then rightward through its vertical loop-form extender. Eventually I decided the abbreviation of my first name was a bit affected (and, anyway, created a lot of unintended confusion) so I expanded it to its full form (Andrew), but maintained the flourish on the final e for longer than I care to admit, until I decided that it, too, needed to go. My signature today is you could say a ruin of its original conception: it’s all that’s left standing.

D

I was always impressed by the illegibility of signatures. The more illegible, the deeper the character of the signatory, or some such.

The signature as hieroglyph? (No.) Ideogram? (No.) Hieroglyph and ideogram lack a connection to the subject who writes it—to represent him/herself. That is, they are not intrinsically deictic.

Logo, trademark? Getting closer. To use contemporary corporate vernacular, perhaps a signature is one’s "brand," though I favor the earlier sense of an identifying mark singed into flesh or wood over its current mercantilistic usage. Is it paper that’s the object of branding, or an idea of some sort (if only the idea that some property or value owned by the brand(ish)er be transferred elsewhere—and no longer be subject to the brand)? An animal is branded to communicate that the animal is property belonging to the owner of the brand. But when I sign my name on a piece of paper, I may be doing something other than laying claim to the piece of paper which now bears my signature.

E

The signature is writing to be seen (as writing): the writing—the branding—foregrounded, and the linguistic values (phonetic representations, graphic signs, and the like) made secondary, all for the purpose of identifying the writing with the writer himself.

A signature is more of an image, something to be looked at, rather than read (if reading refers to the task of decoding the phonetic equivalent of a written string). [2]

If a signature is something to be looked at, it is a different sort of visible object from calligraphic writing. In calligraphy, there needs to be some consistency in the rendering of individual letters, no matter the combinations in which they occur (words, sentence, paragraphs, etc.). [3] Its standard or purpose is beauty or comeliness. It presumably involves an effort to eliminate the contingent effects of the individual writer, except where these are the product of deliberate effort, controlled execution, and aesthetic flair. A signature also requires consistency, but not within the signature itself, rather from one instance of itself to the next. Its standard is distinctiveness, its unique, if not inimitable, aspect.

F

Spoken language (before the age of telecommunication) was local, tied to an occasion. When writing developed, it freed language from the gravitational forces that bind speech to a specific time and place (factors that make speech akin to music). Written documents can travel in space and in time. [4] Or, if you will, writing can transcend time and space. The ability to do so was enhanced by the development of print. Print technology can quickly, relatively cheaply produce multiple copies, but print also manufactured the markets to justify transport to distant places. Furthermore, print freed the written word from the motor and physical limitations and idiosyncrasies of an individual writer or scribe (the "voice," "accent," or "idiolect" of the writer’s handwriting). However it was produced, writing couldn’t easily transcend language, and particularly, the lexicon and grammar used to communicate. Nonetheless it did: along with the emergence of print, there came the development of standard languages. [5]

G

Print is an act of translation of the individual voice or hand into standardized visual forms. The text is foregrounded (i.e., the text as a field of lexically and grammatically-generated and also intertextual meanings [6]); its material source or embodiment "backgrounded" or deemphasized as much as possible. [7] Print as self-effacing or -erasing: Transparent writing: The visible as invisible.

H

The signature is untranslatable.

I

Someone else cannot write your signature. Or, if they do, they are forging it (which is not the same thing as signing it), a crime. They are stealing your signature, your identity, or what? Your agency, your power to say Yes or No, to accept the consequences of your choices; they are making choices in your name and leaving you to be held accountable. They are attributing to you an intention you may not have, undermining thereby the value and purpose of the signature.

J

You can’t write your signature with another name, can you? Your signature is bound to your name, but it’s not your name.

The signature as a token of your own flesh (body, corporeal being) or of your social being. It is the flesh stretched across the skeleton and sinews of your name.

K

What kind of speech act is a signature?

(Name as script. Signature as character, signing as performance.)

How many times and under what heightened circumstances have I, through self-consciousness or whatever stew of conflicts composes performance anxiety, botched my signature, rendering something that, while close, does not strike me as characteristically the same?

Inability to be myself = inability to impersonate myself.

L

Writing, depending on the context, may be more or less legible. Or the writer may be more cognizant of and make a greater effort to produce legible writing. This can apply to the signing of one’s signature. More generally, however, the effort—if it is an effort—goes into reproducing one’s signature—making it identifiable as one’s signature, even though it is not identical with other instances—and even if it is illegible. It is as though a model or type has been created which the signatory then endeavors to approximate.

It’s not that every signature of yours should be, must be identical (that would be impossible [8]), but the signature is an idiom, it tolerates—perhaps requires—a degree of variation. How wide? How is that measured? When does a signature cease to be identifiable?

M

Mimicry of voice.

Impersonation. Impersonation can be a crime. Impersonation in print assumes other forms. E.g., parody. Can a signature be parodied?

N

Can one know how to write, but not have a signature?

Yes, I think so. A language learner may become proficient in reading and writing (at least, spelling) in another language, one written in a non-Latin alphabet, for example, without having a signature in that language. Without existing in the society that speaks this language, what need has she of a signature in that language?

What about the signatures of those who are bilingual and biliterate? Are their signatures the same in the two alphabets, the lines merely refracted through the spectrum of the two writing systems?

But doesn’t everyone have a signature, even if it’s just X? One can have a signature without being able to read or to write. A signature is a social requirement, it gives the signatory a social status, a public face, presence, agency. X suffices, if there are witnesses to the signatory’s signing of it. The "X" presumably needs to be glossed with the written name. The "X" requires the signatures of witnesses to be a signature.

O

Society’s recognition of the individual. Society’s fingerprinting/indexing of the individual. Not to have a signature: a form of anarchy. But the need for a signature probably increased with the flourishing of print and the markets it sustained and which sustained it. For this would have created the need for agreements, contracts, bills of sale, bills of lading, and so forth.

P

Fingerprints might appear to be a surer way of linking a mark with the person who makes it, but actually it is only a surer way of linking the mark with the body, since the marks are made without guarantee of the maker’s intentions (they are obligatory; we make them all the time; I am making them now as I press the keys of my computer to write, but the fingerprints on the keys, which I can’t help but make, are not really part of what I am expressing through the words in this essay).

So, a signature is not a fingerprint, although fingerprints have been used as signatures. Signing is learned behavior. It requires intention. Or, under coercion, the simulation of expressing an intention.

The signature is pushed and pulled by technological innovation (I hesitate to say it is in decline, but there, at last, I have said it). On one side it is threatened by biometric authentication (the use of the body to communicate an intention, a non-arbitary form of identifying a person, though it assumes the Herderian formula: one body, one person) and on the other side by the digital signature.

Signing in blood: the truest biometrical signature? The blood cannot be forged.

But can’t one sign in another’s blood?

Q

The signature as graffiti.

R

The signature is not a name, but a self-reference, a deictic symbol.

It is the name as first person pronoun, but lacking the capacity to “shift.” I say I and so do you, but I sign my name and you yours. (Return to early speech: The toddler says her name instead of I.)

However, the signature of those who can do no better than sign with an X (the non-literate, the disabled) does shift: Anyone can sign X (at least, so long as there are witnesses): X = I.

S

The geography of the signature—where it sits in the document. Its native and natural habitat seems to be the bottom or the end of the page (personal check, credit card receipt, tax return), but there is room for exceptions, e.g., documents requiring multiple signatures.

Why the end? It is outside the text (the assertion, claim, declaration, expression of intent). It is a meta-statement: "I, X, say/assert/claim/declare/intend thus."

Still, why the end or "outside" the text (and not at the beginning or "before")? Is that meant to suggest that the signatory has first read what precedes the signature or uttered it? [9]

Signature dialects: Signing a birthday card (or a personal communication) is different from signing a check. The signature for one would not be appropriate for the other. Perhaps only the latter is really a signature.

T

The signature is a form of routinized contingent behavior: It is through its lack of standardization that a signature is what it is and that it is recognized as such. It transcends (or appears to) the ground of the writing system in which it is rendered (and the expectation that a text rendered in the system be rendered more or less legibly). No, it writes against this system, as if it were a sort of anti-writing or more precisely an ulterior system of writing. (The individual standing up to the system?) The consequences, however, are to bind the individual tightly into a system of laws, obligations, expectations.

U

The signature is the antipode of type. It is most imperious, hieratic, vernacular, idiolectal, infantile. Thereby it, too, may remain current across time and space, current because of its lack of transparency. (The way a song may transcend the language in which it is sung.)

V

The signature as an image, a whole, not something to be dissolved into its parts and reconstituted (or combined in some other way), but to be recognized

W

Print vs. signature: the charisma of words vs. the charisma of the individual.

X

Signatures are not like leopard spots: they can be changed. My mother, upon marrying, took my father’s surname, which meant (among other things) that she signs her name with it. His surname became hers (her "identity"), though she often includes the initial of her maiden name. There are changes in signature that correspond to changes in life status (legal, religious, or otherwise) and changes across the grain of their author’s status.

Y

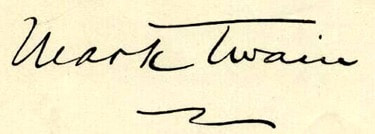

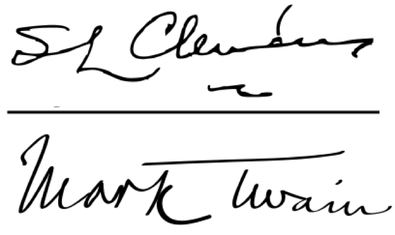

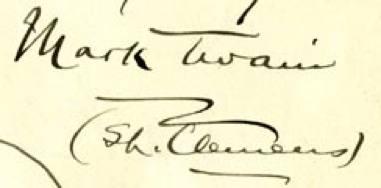

Perhaps I am making much ado about next-to-nothing. Look at the following sampling of Mark Twain’s signatures:

ASunshine

A flourish started from the end of the (final) e and looped leftward back over the h and then rightward through its vertical loop-form extender. Eventually I decided the abbreviation of my first name was a bit affected (and, anyway, created a lot of unintended confusion) so I expanded it to its full form (Andrew), but maintained the flourish on the final e for longer than I care to admit, until I decided that it, too, needed to go. My signature today is you could say a ruin of its original conception: it’s all that’s left standing.

D

I was always impressed by the illegibility of signatures. The more illegible, the deeper the character of the signatory, or some such.

The signature as hieroglyph? (No.) Ideogram? (No.) Hieroglyph and ideogram lack a connection to the subject who writes it—to represent him/herself. That is, they are not intrinsically deictic.

Logo, trademark? Getting closer. To use contemporary corporate vernacular, perhaps a signature is one’s "brand," though I favor the earlier sense of an identifying mark singed into flesh or wood over its current mercantilistic usage. Is it paper that’s the object of branding, or an idea of some sort (if only the idea that some property or value owned by the brand(ish)er be transferred elsewhere—and no longer be subject to the brand)? An animal is branded to communicate that the animal is property belonging to the owner of the brand. But when I sign my name on a piece of paper, I may be doing something other than laying claim to the piece of paper which now bears my signature.

E

The signature is writing to be seen (as writing): the writing—the branding—foregrounded, and the linguistic values (phonetic representations, graphic signs, and the like) made secondary, all for the purpose of identifying the writing with the writer himself.

A signature is more of an image, something to be looked at, rather than read (if reading refers to the task of decoding the phonetic equivalent of a written string). [2]

If a signature is something to be looked at, it is a different sort of visible object from calligraphic writing. In calligraphy, there needs to be some consistency in the rendering of individual letters, no matter the combinations in which they occur (words, sentence, paragraphs, etc.). [3] Its standard or purpose is beauty or comeliness. It presumably involves an effort to eliminate the contingent effects of the individual writer, except where these are the product of deliberate effort, controlled execution, and aesthetic flair. A signature also requires consistency, but not within the signature itself, rather from one instance of itself to the next. Its standard is distinctiveness, its unique, if not inimitable, aspect.

F

Spoken language (before the age of telecommunication) was local, tied to an occasion. When writing developed, it freed language from the gravitational forces that bind speech to a specific time and place (factors that make speech akin to music). Written documents can travel in space and in time. [4] Or, if you will, writing can transcend time and space. The ability to do so was enhanced by the development of print. Print technology can quickly, relatively cheaply produce multiple copies, but print also manufactured the markets to justify transport to distant places. Furthermore, print freed the written word from the motor and physical limitations and idiosyncrasies of an individual writer or scribe (the "voice," "accent," or "idiolect" of the writer’s handwriting). However it was produced, writing couldn’t easily transcend language, and particularly, the lexicon and grammar used to communicate. Nonetheless it did: along with the emergence of print, there came the development of standard languages. [5]

G

Print is an act of translation of the individual voice or hand into standardized visual forms. The text is foregrounded (i.e., the text as a field of lexically and grammatically-generated and also intertextual meanings [6]); its material source or embodiment "backgrounded" or deemphasized as much as possible. [7] Print as self-effacing or -erasing: Transparent writing: The visible as invisible.

H

The signature is untranslatable.

I

Someone else cannot write your signature. Or, if they do, they are forging it (which is not the same thing as signing it), a crime. They are stealing your signature, your identity, or what? Your agency, your power to say Yes or No, to accept the consequences of your choices; they are making choices in your name and leaving you to be held accountable. They are attributing to you an intention you may not have, undermining thereby the value and purpose of the signature.

J

You can’t write your signature with another name, can you? Your signature is bound to your name, but it’s not your name.

The signature as a token of your own flesh (body, corporeal being) or of your social being. It is the flesh stretched across the skeleton and sinews of your name.

K

What kind of speech act is a signature?

(Name as script. Signature as character, signing as performance.)

How many times and under what heightened circumstances have I, through self-consciousness or whatever stew of conflicts composes performance anxiety, botched my signature, rendering something that, while close, does not strike me as characteristically the same?

Inability to be myself = inability to impersonate myself.

L

Writing, depending on the context, may be more or less legible. Or the writer may be more cognizant of and make a greater effort to produce legible writing. This can apply to the signing of one’s signature. More generally, however, the effort—if it is an effort—goes into reproducing one’s signature—making it identifiable as one’s signature, even though it is not identical with other instances—and even if it is illegible. It is as though a model or type has been created which the signatory then endeavors to approximate.

It’s not that every signature of yours should be, must be identical (that would be impossible [8]), but the signature is an idiom, it tolerates—perhaps requires—a degree of variation. How wide? How is that measured? When does a signature cease to be identifiable?

M

Mimicry of voice.

Impersonation. Impersonation can be a crime. Impersonation in print assumes other forms. E.g., parody. Can a signature be parodied?

N

Can one know how to write, but not have a signature?

Yes, I think so. A language learner may become proficient in reading and writing (at least, spelling) in another language, one written in a non-Latin alphabet, for example, without having a signature in that language. Without existing in the society that speaks this language, what need has she of a signature in that language?

What about the signatures of those who are bilingual and biliterate? Are their signatures the same in the two alphabets, the lines merely refracted through the spectrum of the two writing systems?

But doesn’t everyone have a signature, even if it’s just X? One can have a signature without being able to read or to write. A signature is a social requirement, it gives the signatory a social status, a public face, presence, agency. X suffices, if there are witnesses to the signatory’s signing of it. The "X" presumably needs to be glossed with the written name. The "X" requires the signatures of witnesses to be a signature.

O

Society’s recognition of the individual. Society’s fingerprinting/indexing of the individual. Not to have a signature: a form of anarchy. But the need for a signature probably increased with the flourishing of print and the markets it sustained and which sustained it. For this would have created the need for agreements, contracts, bills of sale, bills of lading, and so forth.

P

Fingerprints might appear to be a surer way of linking a mark with the person who makes it, but actually it is only a surer way of linking the mark with the body, since the marks are made without guarantee of the maker’s intentions (they are obligatory; we make them all the time; I am making them now as I press the keys of my computer to write, but the fingerprints on the keys, which I can’t help but make, are not really part of what I am expressing through the words in this essay).

So, a signature is not a fingerprint, although fingerprints have been used as signatures. Signing is learned behavior. It requires intention. Or, under coercion, the simulation of expressing an intention.

The signature is pushed and pulled by technological innovation (I hesitate to say it is in decline, but there, at last, I have said it). On one side it is threatened by biometric authentication (the use of the body to communicate an intention, a non-arbitary form of identifying a person, though it assumes the Herderian formula: one body, one person) and on the other side by the digital signature.

Signing in blood: the truest biometrical signature? The blood cannot be forged.

But can’t one sign in another’s blood?

Q

The signature as graffiti.

R

The signature is not a name, but a self-reference, a deictic symbol.

It is the name as first person pronoun, but lacking the capacity to “shift.” I say I and so do you, but I sign my name and you yours. (Return to early speech: The toddler says her name instead of I.)

However, the signature of those who can do no better than sign with an X (the non-literate, the disabled) does shift: Anyone can sign X (at least, so long as there are witnesses): X = I.

S

The geography of the signature—where it sits in the document. Its native and natural habitat seems to be the bottom or the end of the page (personal check, credit card receipt, tax return), but there is room for exceptions, e.g., documents requiring multiple signatures.

Why the end? It is outside the text (the assertion, claim, declaration, expression of intent). It is a meta-statement: "I, X, say/assert/claim/declare/intend thus."

Still, why the end or "outside" the text (and not at the beginning or "before")? Is that meant to suggest that the signatory has first read what precedes the signature or uttered it? [9]

Signature dialects: Signing a birthday card (or a personal communication) is different from signing a check. The signature for one would not be appropriate for the other. Perhaps only the latter is really a signature.

T

The signature is a form of routinized contingent behavior: It is through its lack of standardization that a signature is what it is and that it is recognized as such. It transcends (or appears to) the ground of the writing system in which it is rendered (and the expectation that a text rendered in the system be rendered more or less legibly). No, it writes against this system, as if it were a sort of anti-writing or more precisely an ulterior system of writing. (The individual standing up to the system?) The consequences, however, are to bind the individual tightly into a system of laws, obligations, expectations.

U

The signature is the antipode of type. It is most imperious, hieratic, vernacular, idiolectal, infantile. Thereby it, too, may remain current across time and space, current because of its lack of transparency. (The way a song may transcend the language in which it is sung.)

V

The signature as an image, a whole, not something to be dissolved into its parts and reconstituted (or combined in some other way), but to be recognized

- as a signature and

- as the signature of a particular known or knowable person.

W

Print vs. signature: the charisma of words vs. the charisma of the individual.

X

Signatures are not like leopard spots: they can be changed. My mother, upon marrying, took my father’s surname, which meant (among other things) that she signs her name with it. His surname became hers (her "identity"), though she often includes the initial of her maiden name. There are changes in signature that correspond to changes in life status (legal, religious, or otherwise) and changes across the grain of their author’s status.

Y

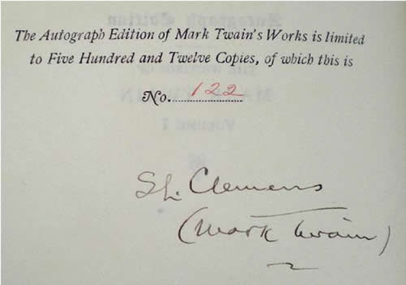

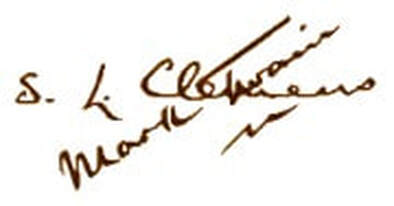

Perhaps I am making much ado about next-to-nothing. Look at the following sampling of Mark Twain’s signatures:

There are many more variations on the web (not including the forgeries). Without knowing much of anything about Mark Twain/Samuel Clemens, one might suppose sometimes he was one, sometimes the other, often both; and when both, his names might receive equal weight or unequal weight. In the last signature reproduced here, do the names receive equal weight or does one cancel the other? If the latter, which name does the cancelling? Or are they reciprocally canceling?

Z

Whether or not one name is cancelling the other or each name is canceling the other, together they form an X, the ultimate symbol of cancellation as such, but also the universal signature. The signature as the cancellation of the signatory’s absence.

Footnotes

[1] It was accompanied by a careful cursive representation of his full-name (probably at the insistence of his apprehensive parents).

[2] Reading is more complicated than that, of course; once one has become a fluent reader, decoding in this sense becomes secondary, a back-up measure, and pattern recognition more important, and more complex. A fluent reader is a reader who takes chances, reads in, reads over, increases the risk of misreading. There may therefore be some fundamental affinities between the pattern recognition of reading and of viewing/recognizing signatures.

[3] Although context may require modification and variants of letters.

[4] Of course, with the invention of recording, telephones, broadcasting, and other forms of telecommunication, what once might have seemed like an axiomatic distinction between writing and speech was shown to be a constitutive element.

[5] Perhaps it’s important to note that spoken language almost by definition tends to involve an effort to surmount the limits of idiosyncratic usage (differences of usage between locations (dialects), class (sociolects), age or generations, but also between grammar, as in the formation of pidgins, creoles and other forms of language contact). The affinities between the poles of the language spectrum are striking.

[6] A text is more than a lexical and grammatical construction: its design is influenced by other language arts, including logic and rhetoric and a variety of literary forms.

[7] Perhaps a typographer wouldn’t see it that way. Furthermore, alongside the particular way in which material form might be considered to be deemphasized, there is an undeniable sense in which it is exacerbated: the mechanical reproduction of the text which makes it available everywhere all the time (not exactly).

[8] And might raise suspicion that a machine was signing for the supposed signatory. See, Charles Hamilton, The Robot that Helped to Make a President: A Reconnaissance into the Mysteries of John F. Kennedy’s Signature, New York: 1965.

[9] It should be noted that there are other geographic considerations that I have all but ignored. "The signature" is not always and everywhere the same thing, and this might raise the question whether the social construction of the person also varies by culture. These subjects, however, seem like the basis for a future study.

Further, just as an individual’s signature is subject to change over time, so, too, does the signature as such have a history. This is especially easy to see in the current so-called "digital age" in which strings of ASCII characters can serve as signatures in the right context.

[10] The website on which this signature appears includes the following disclaimer:

The intention has been to use public domain material, however, it has not always been possible to determine provenance and to verify copyright status. If any material is not in the public domain, it will be withdrawn immediately upon receiving such advise and verification.

In reply my question about the provenance of the signature image, I was informed that there was no record for the source. My own efforts to track one down have not been successful.

[1] It was accompanied by a careful cursive representation of his full-name (probably at the insistence of his apprehensive parents).

[2] Reading is more complicated than that, of course; once one has become a fluent reader, decoding in this sense becomes secondary, a back-up measure, and pattern recognition more important, and more complex. A fluent reader is a reader who takes chances, reads in, reads over, increases the risk of misreading. There may therefore be some fundamental affinities between the pattern recognition of reading and of viewing/recognizing signatures.

[3] Although context may require modification and variants of letters.

[4] Of course, with the invention of recording, telephones, broadcasting, and other forms of telecommunication, what once might have seemed like an axiomatic distinction between writing and speech was shown to be a constitutive element.

[5] Perhaps it’s important to note that spoken language almost by definition tends to involve an effort to surmount the limits of idiosyncratic usage (differences of usage between locations (dialects), class (sociolects), age or generations, but also between grammar, as in the formation of pidgins, creoles and other forms of language contact). The affinities between the poles of the language spectrum are striking.

[6] A text is more than a lexical and grammatical construction: its design is influenced by other language arts, including logic and rhetoric and a variety of literary forms.

[7] Perhaps a typographer wouldn’t see it that way. Furthermore, alongside the particular way in which material form might be considered to be deemphasized, there is an undeniable sense in which it is exacerbated: the mechanical reproduction of the text which makes it available everywhere all the time (not exactly).

[8] And might raise suspicion that a machine was signing for the supposed signatory. See, Charles Hamilton, The Robot that Helped to Make a President: A Reconnaissance into the Mysteries of John F. Kennedy’s Signature, New York: 1965.

[9] It should be noted that there are other geographic considerations that I have all but ignored. "The signature" is not always and everywhere the same thing, and this might raise the question whether the social construction of the person also varies by culture. These subjects, however, seem like the basis for a future study.

Further, just as an individual’s signature is subject to change over time, so, too, does the signature as such have a history. This is especially easy to see in the current so-called "digital age" in which strings of ASCII characters can serve as signatures in the right context.

[10] The website on which this signature appears includes the following disclaimer:

The intention has been to use public domain material, however, it has not always been possible to determine provenance and to verify copyright status. If any material is not in the public domain, it will be withdrawn immediately upon receiving such advise and verification.

In reply my question about the provenance of the signature image, I was informed that there was no record for the source. My own efforts to track one down have not been successful.

Copyright © January 2020 Andrew Sunshine

Andrew Sunshine is the author of Thyrsus and 99 (Linear Arts) and Andra moi (Ambitus Books). His poems have appeared in Literal Latte, Salonika, and Snake Nation, among other journals. He is co-editor (with Donna Jo Napoli) of Tongue’s Palette: Poetry by Linguists and editor of The Alembic Space: Writings on Poetics and Translation by Joseph Malone (Atlantis-Centaur, 2004 and 2006 respectively). Sunshine lives in New York City with his wife and two sons.