KRISTINA MORICONI

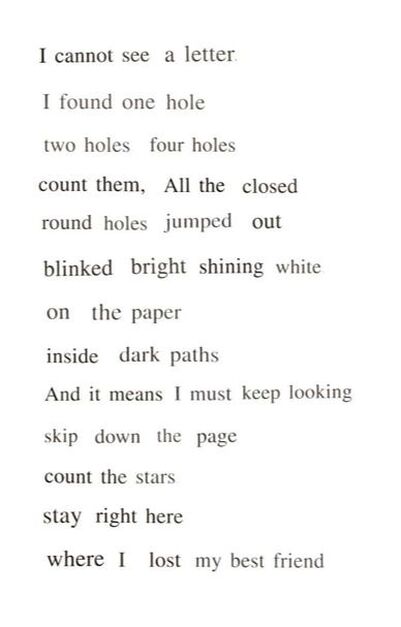

Still Looking

The day begins with a headline. News I skim through, lately, such deep sadness.

In Ukraine’s Bucha,

one woman

is painting flowers

around bullet holes

Her name is Ivanka. She is a volunteer. The town, a suburb of Ukraine’s capitol, a place where

Her name is Ivanka. She is a volunteer. The town, a suburb of Ukraine’s capitol, a place where civilians were massacred, homes bombed, burned to the ground.

Here, Ivanka meets a man whose son was killed, the bullet holes in his fence now a constant reminder of all he has lost. This war, this grief, once inconceivable to him. Too often, there is no way of knowing, no time to prepare.

I wonder if the man’s son once felt safe. If small, incidental worries had been all the man once had.

Early on, as a child, I was unafraid. My life, contained: A house on a suburban street. A backyard enclosed by a fence. Safe, other than my father’s summer struggle with the carpenter bees. I remember how they riddled the fence with deep holes, some tunneling all the way through.

How I plugged them with my fingers sometimes, this tactile need I had back then, to connect. To identify. How, standing back, farther away, still, I saw the holes. As part of the fence first then as a separate pattern of circles I could picture, even without the context of the wood pickets and posts.

My eyes drawn in this way to each negative space. Some filled with darkness. Others, small frames holding fragmented parts of a whole on the other side—green of the neighbor’s grass, yellow of dandelions growing wild.

How, at some point, I stopped seeing the fence at all. How each hole became a microcosm of its own. A place where tiny mandibles had bored through wood. At a rate of roughly one inch every five to six days. A map of both momentum and ruin.

Many years later, with this memory still so sharp in my mind, I think of the man in Bucha, of the holes he sees every day now. Each one, a place where a bullet lodged or passed through. A diagram of violence, cruelty, bloodshed. A daily, inescapable reminder: Here, in this void, or this void, or this void, evidence of what took his son.

Sometimes, remembering can be a subtraction.

It is Ivanka, her heart broken by the man’s story, who begins turning the bullet holes into flowers. Colorful blooms sprouting on shot-up fences—daffodils and daisies, sunflowers poppies and forget-me-nots.

A tessellation of natural forms. Beauty where there’d been only ugliness and pain.

An act of addition.

Later that same day, I pick up the most recent copy of The New Yorker from my coffee table, open to the profile of an artist, Matthew Wong’s Life in Light and Shadow. The painting featured on the first page is titled See You on the Other Side.

Immediately, my eye is pulled to the center of this composition, the stark white of no paint there at all. The striking contrast of a lone figure in the foreground against an utterly blank space.

At the beginning of Wong’s career, the profile says, he was fascinated by voided surfaces. He’d written of his hopes to conjure in his work “the mysterious ghosts of what-has-just-been.”

When I was six, out of necessity, I learned a new way of seeing. On the first day of school, we were assigned partners, and this person was expected to be on our immediate left or right whenever we were told to line up.

Missy DiNatale was my line partner, my first friend. At once, we became inseparable, our days braided. Minutes paired up. Hours interwoven.

One day, Missy was there beside me. Then, she was not.

Soon after, someone told me she’d been hit by a car on her way home from school. No one talked to me about death, though. I heard its name and, inside my six-year-old mind, it seemed immense.

Unfathomable.

Missy was gone. Beside me in line, no one stood.

“Matthew Wong is preoccupied with voids,” the profile in The New Yorker continues. He had written a poem titled The Shape of Silence, containing these lines:

Imagine reading a novel

Where instead of looking at the words

Your gaze was fixed on the spaces

Between them. When you get to the end,

What would you say of what you saw and felt?

Over time, Missy becomes for me a memory, one I construct in a certain way. A kind of photographic image in which the absence of her is captured—in the empty space, a shape forming—the shape of loss, of not-knowing. Of disappearance, of search-for.

A ghost of what-had-just-been.

Back then, in first grade, I learned: Sad things hushed became heavy. But I did not have the language I needed to talk about it. I didn’t have someone who’d listen.

I disappeared, too, into myself, into books. I struggled to read, though. The page, its parade of letters, seemed at times impenetrable to me.

Obstacle.

I wanted more than anything to be in the highest-level reading group.

Overachiever.

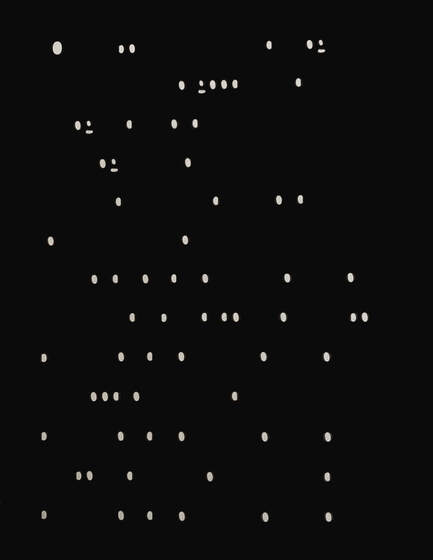

But I wrestled with the words, the way I saw them on the page. My eyes fixated on shapes within letterforms, especially the hollowed-out, empty spaces inside letters like o and p, q and g, b and d.

Overwhelming.

Page-white circles scattered everywhere. How they distracted me. How it took additional time for me to focus, to decipher. To loosen and untangle letters from a strange tapestry of shapes.

I didn’t tell anyone about this. And no one noticed or said anything. Part of me began to think maybe everyone had this same trouble, to some degree. Another part of me was ashamed. I wanted to be a perfect student. So, to overcome it, to compensate, I decided I would simply read more than everyone else.

Later, as an art student in college, I reconnected with those shapes. My second year, Typography I and II, I fell madly in love with fonts, with their families. With the vocabulary of typeface, the anatomy of letterforms.

Perhaps it was my experience as a young reader that made me so curious, so interested in knowing that the enclosed spaces inside letters like o and p was called a counter. And that a counter was created by the curved stroke of a bowl.

I learned about leading and kerning, too, the way each was used to manipulate the space within a text—the gaps, the distance in between.

Acquiring this knowledge let me name what had once tried to defeat me.

Your gaze was fixed on the spaces

Between them.

It began to make sense, what I saw and felt. It, too, was silence.

In first grade, our class library day was Friday. I begged the librarian to let me return my books and take out new ones during the week in between. I wanted so much to tell her why, but I didn’t know what to say. Somehow silence seemed like a better choice than risking the uncertainty I felt choking back my voice.

Silence can be a brief interval.

Or it can stretch out, become a void.

One day, alone in the library, I searched for Frog and Toad Are Friends. It was among my favorites, about best friends who were always there for each other. I suppose I wanted to know more about what that looked like, what that meant. So much about friendship already seemed slippery to me.

Out of reach.

When I brought the book to the librarian’s desk, she slid the library card from its pocket on the inside back cover, waited for me to sign my name.

I saw Missy’s name two lines below, her flawless printing beside tiny numbers of the date stamped in red: the same month she died.

At home, I opened Frog and Toad Are Friends, thought again about Missy, how she once held this book in her hands, once read these words.

I wanted to cry, but I didn’t. Sometimes, instead, I forgot to breathe. My silence felt sharp, like something caught in the throat.

And so, on I went. In search of.

These words I find inside the book I’ve kept since childhood. In silence, I leaf through.

I cut out, collect.

I shift around, reorder.

Reframe.

In Ukraine’s Bucha,

one woman

is painting flowers

around bullet holes

Her name is Ivanka. She is a volunteer. The town, a suburb of Ukraine’s capitol, a place where

Her name is Ivanka. She is a volunteer. The town, a suburb of Ukraine’s capitol, a place where civilians were massacred, homes bombed, burned to the ground.

Here, Ivanka meets a man whose son was killed, the bullet holes in his fence now a constant reminder of all he has lost. This war, this grief, once inconceivable to him. Too often, there is no way of knowing, no time to prepare.

I wonder if the man’s son once felt safe. If small, incidental worries had been all the man once had.

Early on, as a child, I was unafraid. My life, contained: A house on a suburban street. A backyard enclosed by a fence. Safe, other than my father’s summer struggle with the carpenter bees. I remember how they riddled the fence with deep holes, some tunneling all the way through.

How I plugged them with my fingers sometimes, this tactile need I had back then, to connect. To identify. How, standing back, farther away, still, I saw the holes. As part of the fence first then as a separate pattern of circles I could picture, even without the context of the wood pickets and posts.

My eyes drawn in this way to each negative space. Some filled with darkness. Others, small frames holding fragmented parts of a whole on the other side—green of the neighbor’s grass, yellow of dandelions growing wild.

How, at some point, I stopped seeing the fence at all. How each hole became a microcosm of its own. A place where tiny mandibles had bored through wood. At a rate of roughly one inch every five to six days. A map of both momentum and ruin.

Many years later, with this memory still so sharp in my mind, I think of the man in Bucha, of the holes he sees every day now. Each one, a place where a bullet lodged or passed through. A diagram of violence, cruelty, bloodshed. A daily, inescapable reminder: Here, in this void, or this void, or this void, evidence of what took his son.

Sometimes, remembering can be a subtraction.

It is Ivanka, her heart broken by the man’s story, who begins turning the bullet holes into flowers. Colorful blooms sprouting on shot-up fences—daffodils and daisies, sunflowers poppies and forget-me-nots.

A tessellation of natural forms. Beauty where there’d been only ugliness and pain.

An act of addition.

Later that same day, I pick up the most recent copy of The New Yorker from my coffee table, open to the profile of an artist, Matthew Wong’s Life in Light and Shadow. The painting featured on the first page is titled See You on the Other Side.

Immediately, my eye is pulled to the center of this composition, the stark white of no paint there at all. The striking contrast of a lone figure in the foreground against an utterly blank space.

At the beginning of Wong’s career, the profile says, he was fascinated by voided surfaces. He’d written of his hopes to conjure in his work “the mysterious ghosts of what-has-just-been.”

When I was six, out of necessity, I learned a new way of seeing. On the first day of school, we were assigned partners, and this person was expected to be on our immediate left or right whenever we were told to line up.

Missy DiNatale was my line partner, my first friend. At once, we became inseparable, our days braided. Minutes paired up. Hours interwoven.

One day, Missy was there beside me. Then, she was not.

Soon after, someone told me she’d been hit by a car on her way home from school. No one talked to me about death, though. I heard its name and, inside my six-year-old mind, it seemed immense.

Unfathomable.

Missy was gone. Beside me in line, no one stood.

“Matthew Wong is preoccupied with voids,” the profile in The New Yorker continues. He had written a poem titled The Shape of Silence, containing these lines:

Imagine reading a novel

Where instead of looking at the words

Your gaze was fixed on the spaces

Between them. When you get to the end,

What would you say of what you saw and felt?

Over time, Missy becomes for me a memory, one I construct in a certain way. A kind of photographic image in which the absence of her is captured—in the empty space, a shape forming—the shape of loss, of not-knowing. Of disappearance, of search-for.

A ghost of what-had-just-been.

Back then, in first grade, I learned: Sad things hushed became heavy. But I did not have the language I needed to talk about it. I didn’t have someone who’d listen.

I disappeared, too, into myself, into books. I struggled to read, though. The page, its parade of letters, seemed at times impenetrable to me.

Obstacle.

I wanted more than anything to be in the highest-level reading group.

Overachiever.

But I wrestled with the words, the way I saw them on the page. My eyes fixated on shapes within letterforms, especially the hollowed-out, empty spaces inside letters like o and p, q and g, b and d.

Overwhelming.

Page-white circles scattered everywhere. How they distracted me. How it took additional time for me to focus, to decipher. To loosen and untangle letters from a strange tapestry of shapes.

I didn’t tell anyone about this. And no one noticed or said anything. Part of me began to think maybe everyone had this same trouble, to some degree. Another part of me was ashamed. I wanted to be a perfect student. So, to overcome it, to compensate, I decided I would simply read more than everyone else.

Later, as an art student in college, I reconnected with those shapes. My second year, Typography I and II, I fell madly in love with fonts, with their families. With the vocabulary of typeface, the anatomy of letterforms.

Perhaps it was my experience as a young reader that made me so curious, so interested in knowing that the enclosed spaces inside letters like o and p was called a counter. And that a counter was created by the curved stroke of a bowl.

I learned about leading and kerning, too, the way each was used to manipulate the space within a text—the gaps, the distance in between.

Acquiring this knowledge let me name what had once tried to defeat me.

Your gaze was fixed on the spaces

Between them.

It began to make sense, what I saw and felt. It, too, was silence.

In first grade, our class library day was Friday. I begged the librarian to let me return my books and take out new ones during the week in between. I wanted so much to tell her why, but I didn’t know what to say. Somehow silence seemed like a better choice than risking the uncertainty I felt choking back my voice.

Silence can be a brief interval.

Or it can stretch out, become a void.

One day, alone in the library, I searched for Frog and Toad Are Friends. It was among my favorites, about best friends who were always there for each other. I suppose I wanted to know more about what that looked like, what that meant. So much about friendship already seemed slippery to me.

Out of reach.

When I brought the book to the librarian’s desk, she slid the library card from its pocket on the inside back cover, waited for me to sign my name.

I saw Missy’s name two lines below, her flawless printing beside tiny numbers of the date stamped in red: the same month she died.

At home, I opened Frog and Toad Are Friends, thought again about Missy, how she once held this book in her hands, once read these words.

I wanted to cry, but I didn’t. Sometimes, instead, I forgot to breathe. My silence felt sharp, like something caught in the throat.

And so, on I went. In search of.

These words I find inside the book I’ve kept since childhood. In silence, I leaf through.

I cut out, collect.

I shift around, reorder.

Reframe.

Still looking.

It returns to me, what I once took in when I glimpsed the page.

It returns to me, what I once took in when I glimpsed the page.

I keep thinking about the link between silence and erasure. How both are an absence, a lack-- one of sound, one of image. The way silence insists on its own voice anyway, a constellation of thoughts. And how erasure becomes its own interpretation, something wholly new.

Still looking.

Later, sitting in a courtyard beside a coffee shop, I hold onto my mug, notice the counter inside the handle’s bowl, its negative space enclosed, filled up with what exists just beyond where I sit: the terra cotta brick of pathway, the gray-white clouds of more-distant sky.

In this moment, I think of Georgia O’Keeffe.

When I started painting the pelvis bones I was most interested in the holes

in the bones—what I saw through them—particularly the blue…that blue

that will always be there as it is now after all man’s destruction is finished.

Outside, where I sit drinking coffee, a pattern catches my eye:

Still looking.

Later, sitting in a courtyard beside a coffee shop, I hold onto my mug, notice the counter inside the handle’s bowl, its negative space enclosed, filled up with what exists just beyond where I sit: the terra cotta brick of pathway, the gray-white clouds of more-distant sky.

In this moment, I think of Georgia O’Keeffe.

When I started painting the pelvis bones I was most interested in the holes

in the bones—what I saw through them—particularly the blue…that blue

that will always be there as it is now after all man’s destruction is finished.

Outside, where I sit drinking coffee, a pattern catches my eye:

And I am reminded of the war in Ukraine, pulled back to the woman in the newspaper headline who is painting flowers where bullets passed through buildings and fences.

And, now, in another school classroom here in this country: Circles drawn to count circles. To tally the number of shots it took to cut-short twenty-one lives.

These maps and diagrams. Statistics. These sequences and similarities. And, once again, the tears come, to remind me I am still carrying the untold weight of sadness.

In every loss, Missy. Again and again, I relive the unknowing.

My silence, a scream.

Erasure as the taking of a life.

Erasure as a way of grieving, of reconfiguring what remains.

There.

Here.

No one else notices it that evening, the hornet’s nest just above our heads, its teardrop shape attached to the ceiling of my granddaughters’ backyard fort. It is the dark circle of its singular entrance at the bottom that I see first.

Zero-in-on.

Then, a much smaller, darker hole right beside the nest. This goes deep into a circle-knot in the planks of cedar, scraped from here by the queen, mixed with saliva in her mouth to form the paper pulp of the nest walls.

Where they see danger, I stare, in awe of the architecture, its symmetry. The tug of my eye to these tiny apertures.

And, now, in another school classroom here in this country: Circles drawn to count circles. To tally the number of shots it took to cut-short twenty-one lives.

These maps and diagrams. Statistics. These sequences and similarities. And, once again, the tears come, to remind me I am still carrying the untold weight of sadness.

In every loss, Missy. Again and again, I relive the unknowing.

My silence, a scream.

Erasure as the taking of a life.

Erasure as a way of grieving, of reconfiguring what remains.

There.

Here.

No one else notices it that evening, the hornet’s nest just above our heads, its teardrop shape attached to the ceiling of my granddaughters’ backyard fort. It is the dark circle of its singular entrance at the bottom that I see first.

Zero-in-on.

Then, a much smaller, darker hole right beside the nest. This goes deep into a circle-knot in the planks of cedar, scraped from here by the queen, mixed with saliva in her mouth to form the paper pulp of the nest walls.

Where they see danger, I stare, in awe of the architecture, its symmetry. The tug of my eye to these tiny apertures.

My own way of seeing, finally, years later, diagnosed. Eye tracking studies. Visual encoding reports: Interrupted processing. An obsessive focus on minute detail. Compulsive pattern-making, outline-tracing.

What feels to me like control, though it is actually a lack of control. A state of being out of control. It is real. It is hard for me to overcome. A lifelong effort to understand myself, my way of relating to what surrounds me. The way I take it all in, find shapes and patterns. Like Matthew Wong, preoccupied with voids.

Even when I try to unwind, even in the midst of holding a yoga pose, Seated Spinal Twist, left heel folded to rest against right hip, right foot stepped over left leg, planted firmly on the floor, lifting the lumbar spine as I press the sit-bones down—even then I note the space of counter formed by the bowl of my lower body. How it forms a triangle, how it frames the stone Buddha I face at the front of the room, to remind me: Inhale. Exhale.

The yoga instructor teaches the class about the throat chakra, how it is defined by the element of space, associated with the color blue.

“Blue allows the body and mind to experience stillness,” she says. “Close your eyes. Imagine the brightest blue.”

I can think only of Georgia O’Keeffe, her blue sky through empty sockets. Space opening, expanding. The universe through the portal of a bone.

It is Buddha who once said: Silence isn’t empty. It is full of answers.

Quietly, I wait.

What feels to me like control, though it is actually a lack of control. A state of being out of control. It is real. It is hard for me to overcome. A lifelong effort to understand myself, my way of relating to what surrounds me. The way I take it all in, find shapes and patterns. Like Matthew Wong, preoccupied with voids.

Even when I try to unwind, even in the midst of holding a yoga pose, Seated Spinal Twist, left heel folded to rest against right hip, right foot stepped over left leg, planted firmly on the floor, lifting the lumbar spine as I press the sit-bones down—even then I note the space of counter formed by the bowl of my lower body. How it forms a triangle, how it frames the stone Buddha I face at the front of the room, to remind me: Inhale. Exhale.

The yoga instructor teaches the class about the throat chakra, how it is defined by the element of space, associated with the color blue.

“Blue allows the body and mind to experience stillness,” she says. “Close your eyes. Imagine the brightest blue.”

I can think only of Georgia O’Keeffe, her blue sky through empty sockets. Space opening, expanding. The universe through the portal of a bone.

It is Buddha who once said: Silence isn’t empty. It is full of answers.

Quietly, I wait.

Copyright © December 2022 Kristina Moriconi

|

Kristina Moriconi is a writer and visual artist whose work has appeared in a variety of literary journals and magazines including The Comstock Review, december, One Art, Bellevue Literary Review, and The MacGuffin. She is the winner of Terrain.org’s 11th Annual Nonfiction Contest (2021) and her lyric narrative In the Cloakroom of Proper Musings was published by Atmosphere Press in August 2020. She lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with her husband and two dogs.

|