J.M. FARKAS

First Mindedness, Second Language

I love gold.

I wish I had flowers.

I love cold water.

I love movies.

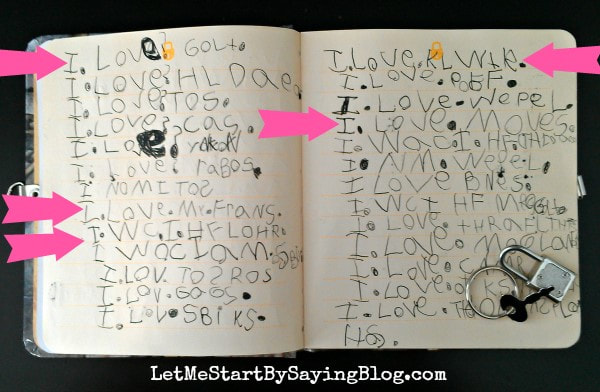

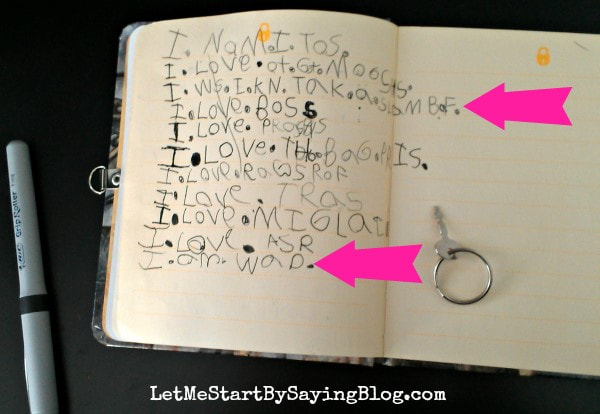

Recently, I came across an article online for which the author received many nasty comments. It’s called: “What I Found in My 5-Year-Old Daughter’s Diary.” In it the author writes: “She has been asking for a kid’s diary for a while now. Her brother gave her a spare he had, and she has been announcing on a daily basis, ‘Do NOT look at me, Mama. I’m writing in my diary.' She keeps the key on a ring on her finger and even chose a special pen. I wondered what she was writing in there. She’s almost 6 years old…Curiosity got the best of me, and with a heavy, worried heart, I unlocked her diary to see what was inside.”

This is what the mother found:

I love gold.

I wish I had flowers.

I love cold water.

I love movies.

Recently, I came across an article online for which the author received many nasty comments. It’s called: “What I Found in My 5-Year-Old Daughter’s Diary.” In it the author writes: “She has been asking for a kid’s diary for a while now. Her brother gave her a spare he had, and she has been announcing on a daily basis, ‘Do NOT look at me, Mama. I’m writing in my diary.' She keeps the key on a ring on her finger and even chose a special pen. I wondered what she was writing in there. She’s almost 6 years old…Curiosity got the best of me, and with a heavy, worried heart, I unlocked her diary to see what was inside.”

This is what the mother found:

Her daughter had been “practicing sounding out words and spelling them phonetically by making a long list of all the things she loves, all the things that make her happy.”

“I love gold. I love my friends. I wish I had flowers. I love cold water. I love movies." She wants to be a better speller, a better writer, a better reader, and the first thing that comes to her to write down is the love she has for so many people and things around her. The things she’d love to experience. The things she loves about herself. "I wish I can take a slime bath. I am weird.”

“I love gold. I love my friends. I wish I had flowers. I love cold water. I love movies." She wants to be a better speller, a better writer, a better reader, and the first thing that comes to her to write down is the love she has for so many people and things around her. The things she’d love to experience. The things she loves about herself. "I wish I can take a slime bath. I am weird.”

The response to this article was very harsh and extensive, totaling 39 pages. Anonymous commenters were horrified that the mother had broken into her daughter’s diary, only to then further betray her privacy and trust with such a public display. They called this mother-author: Big Brother, a cyber-bully. One person wrote: “This girl will hate her disrespectful, meddling mother soon. Rightfully so.” Even those who had the audacity to admit that they enjoyed article, were subject to a tongue-lashing. When one woman wrote that the daughter’s diary was heartwarming, someone wrote back: “May you never have children.”

I guess according to the Virtual Haters and Online Morality Police, I too should be condemned, because I was quite moved by the daughter’s diary. Yes, there was a part of me that just thought it was absolute sweetness, but there was something deeper, more stirring, and I wanted to figure out why: Why do I love this? Why am I so moved by the misspelled desires of a little girl?

One of the reasons is because I knew that what I was reading was meant to be a secret. A secret is twinkly. It is forbidden. It means someone is lonely. It sings that dark song: shhhhhhh. Mary Ruefle has an incredible lecture on this topic in her book, Madness, Rack & Honey, and I recommend you go read it. I have also carefully placed some secrets inside of this essay. See how I dangle them in front of you? I am trying to woo you with something shiny.

Writing has always been a secretive act for me. I believe one of the reasons I started writing is because I was often bored and lonely as a child. In graduate school, I was very reluctant to share my own work and never read at a student reading. Except for workshop, most of my classmates had never seen or heard a single poem that I had written.

Although, I am very lucky to have parents who are supportive of my artistic desires, I mostly do not let them read any of my poems. In my own way, I have been saying the exact same thing as this child: “Don’t look at me, Mama. I’m writing.”

I feel such a twinness with this little girl. In fact, at this point, I would like to give this almost-six-year-old a name. Because we give names to what we love. Let’s call her Lucy. And like Lucy, I also like to write with a special fine-point pen. I love how careful and determined Lucy is. How she keeps the key to her diary on her little ring finger. I have an inexplicable affinity for keys, and I own several necklaces with keys dangling from them. Like secrets in the light, keys might wink at you. I’m not kidding when I say that Lucy also covers some very similar themes and emotional landscapes. Goldenness, water, movies. These are some of my personal obsessions or repetitive images. The only difference is that Lucy covers the same territory as I do, in a much more economical way. Truth be told, I would also like to take a slime bath. I really would.

Also, look at Lucy’s periods! How round, rotund, and proud they are. How emphatic Lucy is when it comes to ending her sentences. I imagine that Lucy must have started out with a small dot, and then went round and round and round the center, until she established a black little ball of punctuation that absolutely delighted her. Michaux in his essay on children’s drawings says: “At no time more than early childhood is there so strong a sense of what is circular, of things that make a circuit, in which are contained departure and return...the circle, which is the shape both of the surging forward and of being safe.”

But what I love most about this diary entry is that it is riddled with misspellings. It is so gloriously-incorrect, brimming with ignorance and ineptitude. I realized that if the secret words of this little girl were spelled correctly, I would love this diary, this Lucy, a little bit less.

I have a secret to tell you right now.

When someone is so excellent at an activity, I might admire her. I am often also jealous. But when someone doesn’t know what she is doing or exposes her vulnerability, I find this more interesting, and certainly more endearing. (Nobody likes a know-it-all.) In an oddly awesome essay by Paul Valery, called “Seashells,” the poet investigates and ruminates wildly on the subject of these “privileged objects,” which he admits he knows nothing about. He writes: “In the matter of shells, then, I did my best to define my ignorance, to organize it, and above all to preserve it.” Something about seashells attracts poets: Pablo Neruda kept a collection of them, as did William Wordsworth, Cavafy, and Whitman; all wrote about the wonders of malacology. The Seashell Game is an anthology compiled by the Japanese poet, Bashō, in 1672. It is Bashō's earliest known book, and the only book he published in his own name. In it two haikus are followed by critical commentary and Bashō acts as referee for a haiku contest. The format is based on a children's game where two seashells were placed side by side and compared.

In Valery’s “Sea Shells,” he also expresses a dislike for know-it-alls. He writes: “Ignorance is a treasure of infinite price that most men squander, when they should cherish its least fragments; some ruin it by educating themselves, others, unable so much as to conceive of making use of it, let it waste away. Quite on the contrary, we should search for it assiduously in what we think we know best. Leaf through a dictionary or try to make one, and you will find that every word covers and masks a well so bottomless that the questions you toss into it arouse no more than an echo.”

I love that Valery directs us to make our own dictionaries. Immediately I thought of how amazing an incorrect dictionary could be. Lo and behold, Google let me know that this already exists online at Unwords.com. Here’s a sampling:

1. B+ stampede (bē plŭs stăm-pēd')

a. (n.) The attempt by half the classroom to claim the paper with no name on it.

2. baboon (bă-bün)

a. (n.) Possibly the highest state of being drunk one can achieve. Example: Dang man, you're a full-out baboon!

The peculiarity of Valery’s essay immediately intrigued me. Weird recognizes weird. But I also love how this meditation is just a more grown-up, verbal expression of the simple, childhood desire to collect seashells on the beach. To really look at them. In essence, Valery reacquaints himself with the wonder of these objects. And wonder is preserved by not knowing.

Children are experts in wonder, ineptitude, bungling, and unknowing. Michaux writes: “The child’s deficiencies are what constitutes his genius.” This is one of the reason why I so enjoyed the following title of an article on the Poetry Foundation’s Harriet poetry blog. It’s called: “The Average Fourth Grader is a Better Poet Than You.” While in graduate school, the author, Hannah Gamble worked as a writer in residence for Writers in the Schools. She visited third, fourth, and fifth grade classrooms. Here are some of the lines written by the students:

“The life of my heart is crimson.”

[Writing about a family member's recent death:]

“My brother went down/ to the river

and put dirt on.”

“Peace be a song,

silver pool of sadness”

“Away went a dull winter wind

that rocked harshly, and bent you said,

‘Father, father’.”

[Writing about a terminal illness:]

“I am feeling burdened

and I taste milk……

I mumble, ‘Please,

please run away.’

But it lives where I live.”

“The owls of midnight hoot like me

shutting the door to nothing.”

[Writing about life as a movie:]

“The choir enters, and the director screams

‘Sing with more terror!!!’”

“I have provisions. Binary muffins.

It’s an in/out/in/out kind of universe.

We cannot help you,

this is a universe factory.

A sound of rolling symbols.

Disappearing rocks, screams of lizards.

Sanity must prevail. Save vs. Do Not.”

“I, the star god,

take bones from the

underworlds of past times

to create mankind.”

Gamble writes: “These young writers are addressing subjects that still obsess poets fifty years older: sadness, death, love, responsibility, aging, family, loneliness, and refuge…and they are addressing these subjects in language that is new, and thus has the power to emotionally effect a well-seasoned (/jaded) reader. The average fourth grader is able to do this because she hasn’t been alive long enough to know how to do it (and by “it” I mean talk about the world) any other way.

The incredibly sad thing about this article is when the author shares samples of student work from older children. As the young writer ages, the writing is less interesting: “By middle school/high school, the average student has learned how normal people talk. The resulting langue is underwhelming and predictable—the safe regurgitation of a thoroughly socialized consciousness. The average older student’s poems are heavy with allegiance to a limited view of reality, the average younger writer’s vision of the world is nimble and surprising—bizarre, yet true.”

If you are looking for an ego boost, apparently this essay will not help you. In addition to elementary school children, you know who also might write better poems in English than you do? People who can’t speak English.

The following poem was written by a Japanese student named, Kiyoe, who was learning to speak English as a second language. I first encountered it about ten years ago and felt instantly and physically seared by its loneliness. I have been looking for it ever since. Across all this time, I could not forget this language.

It’s Poem English School Time

School rest time over and over again look for you

simply appear and simply disappear

that moment smile face and gently think was

as prince appear and as prince disappear

that moment glad and sad think was

and over and over again once more show me simple face

Everybody make noise school is meeting and parting place

but anyone anybody don’t regret so.

because All men have be different

school happy time also certain.

school uninteresting time also certain.

so was know love.

I is anybody love?

so I want. to love to love.

love time sometimes is stop.

school time one after another pass even if speak.

that one day new love find.

school time. only one self look hard

and then sometimes. time is stop.

school time love time is stop.

leave that day is love don’t be.

find my love time.

school time one after another pass even if speak.

school time only one self look hard.

school time love time is stop.

school time is too poor.

school time is too sob.

school time certainly is stop.

don’t forget this language.

I was so thrilled to find this poem again in Dean Young’s book The Art of Recklessness. And here is my second secret: an ulterior motive of this essay was simply to share this poem with you. Because I love it. And just like Lucy’s mother, sometimes I just can’t keep the things I love to myself.

Again, in this poem, it is the unknowing and “wrongness” of the language that move me. Dean Young writes: “the grammatical awkwardness, the lexical wobble, the incompletions and aporia, all convey an unmistakable emotive immediacy. There is work being done here but it conveys liberty through its very errors. What logically is the breakdown of proficiency, of know-how, is productive of an elegant elegiac freshness. The first-mindedness of this poet with this language is indeed something that should not be forgotten. Our language is always a second language and its expressivity resides not just in our proficiency with it but in our playful struggle and ineptitude. Our mistakes are truthful; their music need not be overruled.”

So what’s an aspiring poet to do? We cannot go back in time and become children again. We cannot unlearn our language. How can we recreate or simulate this playful struggle? How can we again reclaim our first-mindedness?

I believe translation is one of the most exciting and mysterious ways to access your first-mind. I insist that you try it out. I insist that you engage with text in another language, especially if you do not speak this language. I urge you not to be afraid of what you do not understand. As Jack Spicer writes in one of the letters that make up his irreverent and excellent translation and correspondence with an already-dead Lorca: “When I translate one of your poems and I come across words I do not understand, I always guess at their meanings. I am inevitably right. A really perfect poem (no one has yet written one) could be perfectly translated by a person who did not know one word of the language it was written in. A really perfect poem has an infinitely small vocabulary.” Spicer takes his naughtiness even further by writing the introduction to his translation of Lorca as if he were Lorca, who I repeat, is dead: “Frankly I was surprised when Mr. Spicer asked me to write an introduction to this volume. My reaction to the manuscript he sent me (and to the series of letters that are now a part of it) was and is fundamentally unsympathetic. It seems to me the waste of a considerable talent on something which is not worth doing.”

*

For the past few years, I have been obsessed with translation. When I started studying poetry seriously, I honestly did not know that you can translate a poem without speaking the language. I was always so impressed with the number of contemporary poets who I wrongly assumed were bilingual. Once I knew better, I sought out Bernadette Mayer’s Catullus, Daniel Ladinsky’s Rumi, and Jane Hirshfield’s stunning tanka.

Another reason I became I transfixed by translation is because I found someone to share my obsession. On almost a daily basis, I had been corresponding over email with Nashwa, a poet-friend & translator, about the intricacies of translation. We have endlessly debated a poet’s fidelity and responsibility to the source material—poets those like Spicer, who take tremendous liberties. We talk about what translators choose to remain faithful to, and why. How they can be boldly irreverent or perhaps wildly irresponsible with language. Whether these poems are truly translations or adaptations or something else entirely.

Translating also became a very personal endeavor for me. As a first-generation American, I have grown up in a household of parents and grandparents who speak Hungarian. Although they won’t admit to it, I always felt like the adults purposefully kept this language from me. Yes, it was a way for them to talk about me in front of my face without my knowing, but I always knew there was also something darker, something sadder in their withholding. Often it is the secrets, those exact things that parents try to keep from their children that their kids are most attuned to.

Hungarian is the language of my parents and grandparents’ childhoods. And their childhoods were filled with unspeakable suffering. All four of my grandparents are survivors of the Holocaust. After the war, my parents were raised in Communist countries. My grandfather would be taken away for months at a time by the Secret Police. If my father misbehaved in school, they shaved his head. My grandmother who helped raise me and picked me up every day from school, who everyone calls Ma, was only thirteen years old when she went to Auschwitz. She lost every single person in her family. So for me, the Hungarian language has a secret language inside of it. It is a barbed wire language. It is a language of the unsayable. In her book, Children of the Holocaust, Helen Epstein, discusses this unspeakable legacy of being the daughter of Holocaust survivors. She refers to it as her “iron box”:

I guess according to the Virtual Haters and Online Morality Police, I too should be condemned, because I was quite moved by the daughter’s diary. Yes, there was a part of me that just thought it was absolute sweetness, but there was something deeper, more stirring, and I wanted to figure out why: Why do I love this? Why am I so moved by the misspelled desires of a little girl?

One of the reasons is because I knew that what I was reading was meant to be a secret. A secret is twinkly. It is forbidden. It means someone is lonely. It sings that dark song: shhhhhhh. Mary Ruefle has an incredible lecture on this topic in her book, Madness, Rack & Honey, and I recommend you go read it. I have also carefully placed some secrets inside of this essay. See how I dangle them in front of you? I am trying to woo you with something shiny.

Writing has always been a secretive act for me. I believe one of the reasons I started writing is because I was often bored and lonely as a child. In graduate school, I was very reluctant to share my own work and never read at a student reading. Except for workshop, most of my classmates had never seen or heard a single poem that I had written.

Although, I am very lucky to have parents who are supportive of my artistic desires, I mostly do not let them read any of my poems. In my own way, I have been saying the exact same thing as this child: “Don’t look at me, Mama. I’m writing.”

I feel such a twinness with this little girl. In fact, at this point, I would like to give this almost-six-year-old a name. Because we give names to what we love. Let’s call her Lucy. And like Lucy, I also like to write with a special fine-point pen. I love how careful and determined Lucy is. How she keeps the key to her diary on her little ring finger. I have an inexplicable affinity for keys, and I own several necklaces with keys dangling from them. Like secrets in the light, keys might wink at you. I’m not kidding when I say that Lucy also covers some very similar themes and emotional landscapes. Goldenness, water, movies. These are some of my personal obsessions or repetitive images. The only difference is that Lucy covers the same territory as I do, in a much more economical way. Truth be told, I would also like to take a slime bath. I really would.

Also, look at Lucy’s periods! How round, rotund, and proud they are. How emphatic Lucy is when it comes to ending her sentences. I imagine that Lucy must have started out with a small dot, and then went round and round and round the center, until she established a black little ball of punctuation that absolutely delighted her. Michaux in his essay on children’s drawings says: “At no time more than early childhood is there so strong a sense of what is circular, of things that make a circuit, in which are contained departure and return...the circle, which is the shape both of the surging forward and of being safe.”

But what I love most about this diary entry is that it is riddled with misspellings. It is so gloriously-incorrect, brimming with ignorance and ineptitude. I realized that if the secret words of this little girl were spelled correctly, I would love this diary, this Lucy, a little bit less.

I have a secret to tell you right now.

When someone is so excellent at an activity, I might admire her. I am often also jealous. But when someone doesn’t know what she is doing or exposes her vulnerability, I find this more interesting, and certainly more endearing. (Nobody likes a know-it-all.) In an oddly awesome essay by Paul Valery, called “Seashells,” the poet investigates and ruminates wildly on the subject of these “privileged objects,” which he admits he knows nothing about. He writes: “In the matter of shells, then, I did my best to define my ignorance, to organize it, and above all to preserve it.” Something about seashells attracts poets: Pablo Neruda kept a collection of them, as did William Wordsworth, Cavafy, and Whitman; all wrote about the wonders of malacology. The Seashell Game is an anthology compiled by the Japanese poet, Bashō, in 1672. It is Bashō's earliest known book, and the only book he published in his own name. In it two haikus are followed by critical commentary and Bashō acts as referee for a haiku contest. The format is based on a children's game where two seashells were placed side by side and compared.

In Valery’s “Sea Shells,” he also expresses a dislike for know-it-alls. He writes: “Ignorance is a treasure of infinite price that most men squander, when they should cherish its least fragments; some ruin it by educating themselves, others, unable so much as to conceive of making use of it, let it waste away. Quite on the contrary, we should search for it assiduously in what we think we know best. Leaf through a dictionary or try to make one, and you will find that every word covers and masks a well so bottomless that the questions you toss into it arouse no more than an echo.”

I love that Valery directs us to make our own dictionaries. Immediately I thought of how amazing an incorrect dictionary could be. Lo and behold, Google let me know that this already exists online at Unwords.com. Here’s a sampling:

1. B+ stampede (bē plŭs stăm-pēd')

a. (n.) The attempt by half the classroom to claim the paper with no name on it.

2. baboon (bă-bün)

a. (n.) Possibly the highest state of being drunk one can achieve. Example: Dang man, you're a full-out baboon!

The peculiarity of Valery’s essay immediately intrigued me. Weird recognizes weird. But I also love how this meditation is just a more grown-up, verbal expression of the simple, childhood desire to collect seashells on the beach. To really look at them. In essence, Valery reacquaints himself with the wonder of these objects. And wonder is preserved by not knowing.

Children are experts in wonder, ineptitude, bungling, and unknowing. Michaux writes: “The child’s deficiencies are what constitutes his genius.” This is one of the reason why I so enjoyed the following title of an article on the Poetry Foundation’s Harriet poetry blog. It’s called: “The Average Fourth Grader is a Better Poet Than You.” While in graduate school, the author, Hannah Gamble worked as a writer in residence for Writers in the Schools. She visited third, fourth, and fifth grade classrooms. Here are some of the lines written by the students:

“The life of my heart is crimson.”

[Writing about a family member's recent death:]

“My brother went down/ to the river

and put dirt on.”

“Peace be a song,

silver pool of sadness”

“Away went a dull winter wind

that rocked harshly, and bent you said,

‘Father, father’.”

[Writing about a terminal illness:]

“I am feeling burdened

and I taste milk……

I mumble, ‘Please,

please run away.’

But it lives where I live.”

“The owls of midnight hoot like me

shutting the door to nothing.”

[Writing about life as a movie:]

“The choir enters, and the director screams

‘Sing with more terror!!!’”

“I have provisions. Binary muffins.

It’s an in/out/in/out kind of universe.

We cannot help you,

this is a universe factory.

A sound of rolling symbols.

Disappearing rocks, screams of lizards.

Sanity must prevail. Save vs. Do Not.”

“I, the star god,

take bones from the

underworlds of past times

to create mankind.”

Gamble writes: “These young writers are addressing subjects that still obsess poets fifty years older: sadness, death, love, responsibility, aging, family, loneliness, and refuge…and they are addressing these subjects in language that is new, and thus has the power to emotionally effect a well-seasoned (/jaded) reader. The average fourth grader is able to do this because she hasn’t been alive long enough to know how to do it (and by “it” I mean talk about the world) any other way.

The incredibly sad thing about this article is when the author shares samples of student work from older children. As the young writer ages, the writing is less interesting: “By middle school/high school, the average student has learned how normal people talk. The resulting langue is underwhelming and predictable—the safe regurgitation of a thoroughly socialized consciousness. The average older student’s poems are heavy with allegiance to a limited view of reality, the average younger writer’s vision of the world is nimble and surprising—bizarre, yet true.”

If you are looking for an ego boost, apparently this essay will not help you. In addition to elementary school children, you know who also might write better poems in English than you do? People who can’t speak English.

The following poem was written by a Japanese student named, Kiyoe, who was learning to speak English as a second language. I first encountered it about ten years ago and felt instantly and physically seared by its loneliness. I have been looking for it ever since. Across all this time, I could not forget this language.

It’s Poem English School Time

School rest time over and over again look for you

simply appear and simply disappear

that moment smile face and gently think was

as prince appear and as prince disappear

that moment glad and sad think was

and over and over again once more show me simple face

Everybody make noise school is meeting and parting place

but anyone anybody don’t regret so.

because All men have be different

school happy time also certain.

school uninteresting time also certain.

so was know love.

I is anybody love?

so I want. to love to love.

love time sometimes is stop.

school time one after another pass even if speak.

that one day new love find.

school time. only one self look hard

and then sometimes. time is stop.

school time love time is stop.

leave that day is love don’t be.

find my love time.

school time one after another pass even if speak.

school time only one self look hard.

school time love time is stop.

school time is too poor.

school time is too sob.

school time certainly is stop.

don’t forget this language.

I was so thrilled to find this poem again in Dean Young’s book The Art of Recklessness. And here is my second secret: an ulterior motive of this essay was simply to share this poem with you. Because I love it. And just like Lucy’s mother, sometimes I just can’t keep the things I love to myself.

Again, in this poem, it is the unknowing and “wrongness” of the language that move me. Dean Young writes: “the grammatical awkwardness, the lexical wobble, the incompletions and aporia, all convey an unmistakable emotive immediacy. There is work being done here but it conveys liberty through its very errors. What logically is the breakdown of proficiency, of know-how, is productive of an elegant elegiac freshness. The first-mindedness of this poet with this language is indeed something that should not be forgotten. Our language is always a second language and its expressivity resides not just in our proficiency with it but in our playful struggle and ineptitude. Our mistakes are truthful; their music need not be overruled.”

So what’s an aspiring poet to do? We cannot go back in time and become children again. We cannot unlearn our language. How can we recreate or simulate this playful struggle? How can we again reclaim our first-mindedness?

I believe translation is one of the most exciting and mysterious ways to access your first-mind. I insist that you try it out. I insist that you engage with text in another language, especially if you do not speak this language. I urge you not to be afraid of what you do not understand. As Jack Spicer writes in one of the letters that make up his irreverent and excellent translation and correspondence with an already-dead Lorca: “When I translate one of your poems and I come across words I do not understand, I always guess at their meanings. I am inevitably right. A really perfect poem (no one has yet written one) could be perfectly translated by a person who did not know one word of the language it was written in. A really perfect poem has an infinitely small vocabulary.” Spicer takes his naughtiness even further by writing the introduction to his translation of Lorca as if he were Lorca, who I repeat, is dead: “Frankly I was surprised when Mr. Spicer asked me to write an introduction to this volume. My reaction to the manuscript he sent me (and to the series of letters that are now a part of it) was and is fundamentally unsympathetic. It seems to me the waste of a considerable talent on something which is not worth doing.”

*

For the past few years, I have been obsessed with translation. When I started studying poetry seriously, I honestly did not know that you can translate a poem without speaking the language. I was always so impressed with the number of contemporary poets who I wrongly assumed were bilingual. Once I knew better, I sought out Bernadette Mayer’s Catullus, Daniel Ladinsky’s Rumi, and Jane Hirshfield’s stunning tanka.

Another reason I became I transfixed by translation is because I found someone to share my obsession. On almost a daily basis, I had been corresponding over email with Nashwa, a poet-friend & translator, about the intricacies of translation. We have endlessly debated a poet’s fidelity and responsibility to the source material—poets those like Spicer, who take tremendous liberties. We talk about what translators choose to remain faithful to, and why. How they can be boldly irreverent or perhaps wildly irresponsible with language. Whether these poems are truly translations or adaptations or something else entirely.

Translating also became a very personal endeavor for me. As a first-generation American, I have grown up in a household of parents and grandparents who speak Hungarian. Although they won’t admit to it, I always felt like the adults purposefully kept this language from me. Yes, it was a way for them to talk about me in front of my face without my knowing, but I always knew there was also something darker, something sadder in their withholding. Often it is the secrets, those exact things that parents try to keep from their children that their kids are most attuned to.

Hungarian is the language of my parents and grandparents’ childhoods. And their childhoods were filled with unspeakable suffering. All four of my grandparents are survivors of the Holocaust. After the war, my parents were raised in Communist countries. My grandfather would be taken away for months at a time by the Secret Police. If my father misbehaved in school, they shaved his head. My grandmother who helped raise me and picked me up every day from school, who everyone calls Ma, was only thirteen years old when she went to Auschwitz. She lost every single person in her family. So for me, the Hungarian language has a secret language inside of it. It is a barbed wire language. It is a language of the unsayable. In her book, Children of the Holocaust, Helen Epstein, discusses this unspeakable legacy of being the daughter of Holocaust survivors. She refers to it as her “iron box”:

For years it lay there in an iron box, buried so deeply within me that I was never able to find out what it really was. I only knew I was carrying some sort of hazardous explosive material around with me, more secret than sexual matters and more dangerous than ghosts and phantoms. Ghosts have a shape and a name. But what was in my iron box had neither the one nor the other. Whatever it was living inside me was so powerful that words dissolved before they could even describe it.

Ma was one of the most important people in my life. Ma had endured the unimaginable. After Auschwitz, she escaped Hungary during the revolution in the 50s, immigrated to American, and sewed zippers in a sweatshop for a dollar an hour, so that her children could have a better life. And yet, despite her difficult life, Ma was one of the most positive, optimistic, awesome people you will ever meet. If you met her, you would never believe what she went through. She lived in Boca Raton, Florida and conducted a much more active life than most people I know. She swam daily. Practiced yoga, bowled, golfed, played bridge, and gossiped non-stop with her clique of octogenarians that she lovingly called, “the girls.” My first book, not only included an extended dedication to her, my grandmother’s face is on the front cover.

Ma often asked me what the deal is with this “poetry stuff” that I am so interested in. As someone whose life circumstances forced her into a very practical existence, she wanted to know: “what’s the point?” Ma asked me: “but what are you going to DO with it? This poetry.”

And yet for someone who claimed not to understand why I devote my time to poetry, Ma had a remarkably poetic past and memory. Even though Ma never finished the 8th grade, she remembered the poems she learned in her one-room schoolhouse. She remembered them by heart. I especially love the wildly inappropriate poem about an obese prostitute, called: “The Ballad of Fat Margo.”

But there is one poem that she remembered most. The one that made her cry. It is the poem she recited as a little girl when she stood on a table to entertain her entire family for the Jewish holidays, soon before her family was taken away in railway cars. It was a poem that was written in a newspaper. The speaker is a mother addressing god. The line that Ma repeated to me is: “please don’t hurt the children.” Ma remembered that all the adults were crying while she read this poem. But Ma admitted that she did not really understand the words that she spoke. Or why everyone was crying.

I began a quest to track down my grandmother’s poem by the poet, Zseni Varnai. My grandmother warned me that the poem might not have made it through the war. It might not have even been published beyond that little newspaper, and so many books were destroyed. With a little help from Jim, the stellar librarian at Vermont College of Fine Arts, as well as some intense Googling, I was able to track down an anthology of Hungarian poetry that included Zseni Varnai. But the poem I was looking for was not there. Through the Interlibrary Loan, I found Varnai’s biography, written in Hungarian. My grandmother read it for clues. Finally, I thought I tracked down the exact poem I was looking for in a book in a library in England. I harassed the librarians there until they were willing to scan me a copy of this poem in Hungarian. I sent it to my grandmother, and she was shaking when she read it. We found it. This was one of the only things she could hold in her hand that took her right back to her family. I also e-stalked a gracious PhD student, online, who completed her dissertation on Hungarian poetry. She was kind enough to take the time to provide a literal English translation.

But it was together with Ma, that I truly embarked on translation.

What I loved about translating with my grandmother was the unexpected advantage of working with a co-translator who does not have a firm grasp of the English language. Her ineptitude inspired my first-mindedness. Because English is her second language, my grandmother often could not make that leap across two languages to come up with the “right” word. When Ma could not think of the word “bud,” she offered up an infinitely more interesting translation: “the still-closed flower.” And that is the language I used in my translation. Months after my original translation, I employed some “scandalous” translation strategies of my own. I cut the poem by more than half of the words, and re-translated it again. This time, the poem was told from the point of view of the flower.

The call to translate provides a poet with an unbelievably intimate experience with the writer of the original work. I dare say it goes far beyond the act of reading or writing. It is a way to inhabit the language of another poet in an intensely personal manner, and in this way to be less lonely. It is a way to more deeply enter into the Poetic Tradition. In Spicer’s second letter to Lorca, he defines tradition as follows: “It means generations of different poets in different countries patiently telling the same story, writing the same poem, gaining and losing something with each transformation—but of course, never really losing anything.”

Translation is a way to ignite first-mindedness, but it is also a method to do something spookier, namely: commune with the dead. For me, I not only felt like I was in a seance with Zseni Varnai and my grandmother, but also with the family that I lost. Spicer also writes of ghosts. Another poet who communes with the dead and concerns himself with ghosts is Christian Hawkey, in his collection, Ventrakl. Hawkey writes: “Envisioned in the form of a scrapbook, Ventrakl folds poetry, prose, biography, translation practices, and photographic imagery into an innovative collaboration with the 19th/early 20th century Austrian Expressionist poet Georg Trakl.” Like Jack Spicer’s After Lorca, translation is the central mode of composition in this book, and it is also the book's central theme, which Hawkey explores in a surprising array of different genres and modes of writing.

I wanted to share some of Hawkey’s wild translation strategies with you: “Sometimes, inspired by a procedure invented by the poet David Cameron, I typed into Microsoft Word a Trakl poem in German and used the spell check program to produce an initial draft. Other strategies involved typing the poem into an online translation engine and then translating the poem back and forth, line by line, between English or German: or shooting, with a 12 gauge, an open Trakl book from a distance of ten feet, then translating with a dictionary, a remaining page of perforated text. Still other poems were generated by working from a book of Trakl’s poems which I had left outside to decompose over a full year in a glass jar filled with rainwater and leaves and mosquito larvae until its pages, over time, dissolved into words, pieces of words, word-stems, floating up and rearranging themselves on the surface of the jar.”

Perhaps the only warning I can give you about translation is that the experience can become more intense or devastating than you ever imagined, which is actually just more incentive to try it. Spicer writes: “Saying goodbye to a ghost is more final than saying goodbye to a lover. Even the dead return, but a ghost, once loved, departing will never reappear.”

On a lighter note, I really think you should translate because it’s fun. It’s child-like and can feel like really challenging playtime. Spicer writes: “It was a game, I shout to myself. A game…It was a game made out of summer and freedom and a need for poetry that would be more than the expression of my hatreds and desires.” I certainly discovered a playful struggle in the translation process that I could not always recognize in my own writing. What I noticed is that when I am stuck with translation, there is something exciting about what I don’t know and what I am unable to do—the endless possibilities. And one of the reasons I do it is to transfer that feeling to my own work. To find that kind of joy in my own writing, that often feels so much more like struggling. To give this kind of pain a new name, a way to trick myself into loving my own ineptitude as a poet in my own language. I don’t know if I’ve sufficiently convinced you to give translation a go. I bet you someday Lucy would be brave enough to try.

*

This essay was written in the memory of my beloved grandmother and co-translator, Eva Wohlberg Braun (3/13/30-11/19/16)

Ma often asked me what the deal is with this “poetry stuff” that I am so interested in. As someone whose life circumstances forced her into a very practical existence, she wanted to know: “what’s the point?” Ma asked me: “but what are you going to DO with it? This poetry.”

And yet for someone who claimed not to understand why I devote my time to poetry, Ma had a remarkably poetic past and memory. Even though Ma never finished the 8th grade, she remembered the poems she learned in her one-room schoolhouse. She remembered them by heart. I especially love the wildly inappropriate poem about an obese prostitute, called: “The Ballad of Fat Margo.”

But there is one poem that she remembered most. The one that made her cry. It is the poem she recited as a little girl when she stood on a table to entertain her entire family for the Jewish holidays, soon before her family was taken away in railway cars. It was a poem that was written in a newspaper. The speaker is a mother addressing god. The line that Ma repeated to me is: “please don’t hurt the children.” Ma remembered that all the adults were crying while she read this poem. But Ma admitted that she did not really understand the words that she spoke. Or why everyone was crying.

I began a quest to track down my grandmother’s poem by the poet, Zseni Varnai. My grandmother warned me that the poem might not have made it through the war. It might not have even been published beyond that little newspaper, and so many books were destroyed. With a little help from Jim, the stellar librarian at Vermont College of Fine Arts, as well as some intense Googling, I was able to track down an anthology of Hungarian poetry that included Zseni Varnai. But the poem I was looking for was not there. Through the Interlibrary Loan, I found Varnai’s biography, written in Hungarian. My grandmother read it for clues. Finally, I thought I tracked down the exact poem I was looking for in a book in a library in England. I harassed the librarians there until they were willing to scan me a copy of this poem in Hungarian. I sent it to my grandmother, and she was shaking when she read it. We found it. This was one of the only things she could hold in her hand that took her right back to her family. I also e-stalked a gracious PhD student, online, who completed her dissertation on Hungarian poetry. She was kind enough to take the time to provide a literal English translation.

But it was together with Ma, that I truly embarked on translation.

What I loved about translating with my grandmother was the unexpected advantage of working with a co-translator who does not have a firm grasp of the English language. Her ineptitude inspired my first-mindedness. Because English is her second language, my grandmother often could not make that leap across two languages to come up with the “right” word. When Ma could not think of the word “bud,” she offered up an infinitely more interesting translation: “the still-closed flower.” And that is the language I used in my translation. Months after my original translation, I employed some “scandalous” translation strategies of my own. I cut the poem by more than half of the words, and re-translated it again. This time, the poem was told from the point of view of the flower.

The call to translate provides a poet with an unbelievably intimate experience with the writer of the original work. I dare say it goes far beyond the act of reading or writing. It is a way to inhabit the language of another poet in an intensely personal manner, and in this way to be less lonely. It is a way to more deeply enter into the Poetic Tradition. In Spicer’s second letter to Lorca, he defines tradition as follows: “It means generations of different poets in different countries patiently telling the same story, writing the same poem, gaining and losing something with each transformation—but of course, never really losing anything.”

Translation is a way to ignite first-mindedness, but it is also a method to do something spookier, namely: commune with the dead. For me, I not only felt like I was in a seance with Zseni Varnai and my grandmother, but also with the family that I lost. Spicer also writes of ghosts. Another poet who communes with the dead and concerns himself with ghosts is Christian Hawkey, in his collection, Ventrakl. Hawkey writes: “Envisioned in the form of a scrapbook, Ventrakl folds poetry, prose, biography, translation practices, and photographic imagery into an innovative collaboration with the 19th/early 20th century Austrian Expressionist poet Georg Trakl.” Like Jack Spicer’s After Lorca, translation is the central mode of composition in this book, and it is also the book's central theme, which Hawkey explores in a surprising array of different genres and modes of writing.

I wanted to share some of Hawkey’s wild translation strategies with you: “Sometimes, inspired by a procedure invented by the poet David Cameron, I typed into Microsoft Word a Trakl poem in German and used the spell check program to produce an initial draft. Other strategies involved typing the poem into an online translation engine and then translating the poem back and forth, line by line, between English or German: or shooting, with a 12 gauge, an open Trakl book from a distance of ten feet, then translating with a dictionary, a remaining page of perforated text. Still other poems were generated by working from a book of Trakl’s poems which I had left outside to decompose over a full year in a glass jar filled with rainwater and leaves and mosquito larvae until its pages, over time, dissolved into words, pieces of words, word-stems, floating up and rearranging themselves on the surface of the jar.”

Perhaps the only warning I can give you about translation is that the experience can become more intense or devastating than you ever imagined, which is actually just more incentive to try it. Spicer writes: “Saying goodbye to a ghost is more final than saying goodbye to a lover. Even the dead return, but a ghost, once loved, departing will never reappear.”

On a lighter note, I really think you should translate because it’s fun. It’s child-like and can feel like really challenging playtime. Spicer writes: “It was a game, I shout to myself. A game…It was a game made out of summer and freedom and a need for poetry that would be more than the expression of my hatreds and desires.” I certainly discovered a playful struggle in the translation process that I could not always recognize in my own writing. What I noticed is that when I am stuck with translation, there is something exciting about what I don’t know and what I am unable to do—the endless possibilities. And one of the reasons I do it is to transfer that feeling to my own work. To find that kind of joy in my own writing, that often feels so much more like struggling. To give this kind of pain a new name, a way to trick myself into loving my own ineptitude as a poet in my own language. I don’t know if I’ve sufficiently convinced you to give translation a go. I bet you someday Lucy would be brave enough to try.

*

This essay was written in the memory of my beloved grandmother and co-translator, Eva Wohlberg Braun (3/13/30-11/19/16)

Copyright © October 2019 J.M. Farkas

J.M. Farkas is the author of Be Brave: An Unlikely Manual for Erasing Heartbreak—an erasure of Beowulf via blackout poetry. Her poetry appears in Boxcar Poetry Review, Hanging Loose, Painted Bride Quarterly, and Forklift, Ohio, and she has written for The New York Times and Electric Literature. Her next book, How to Be a Poet, is an erasure of Ovid's Ars Amatoria or "The Art of Love." You can find more of her work at www.jmfarkas.com.