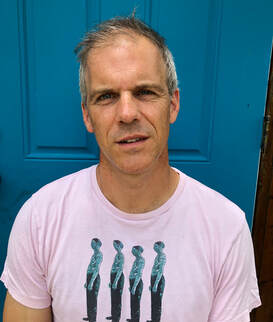

STEINUR BELL

How to Measure Rain

From his hospital bed, Lewis looked at a photograph of his tumor. His tumor was in a silver bowl

and somehow, perhaps in its size and in its watery purple-white color, it reminded him of his mother’s little arthritic fists. Months after she’d died, he had still seen them, a twisted still life, and now he wondered if one had actually returned, reincarnated. An absurd thought, embarrassing, but strange it’d been inside him, for years, he supposed—at first a few disturbed cells, now a fist. He felt nauseous. He looked up at the TV to avoid the smiling surgeon, who held out another photograph.

“One pound, three ounces,” the surgeon said. “You’re a lighter man.”

A Land Rover commercial played: giraffes bounded across the savannah. Terrified they must have been, racing from the cameramen in their loud, pursuing vehicles.

“I cut out a nine pounder once. That was my biggest.”

“Is it still raining out there?” Lewis asked.

“Of course it’s raining.”

The meteorologists had predicted this, the thirty-second consecutive day of measurable rain, now just two days shy of a record. Someone had walked out of an office near the airport, checked the special receptacle, perhaps had shaken his head in disbelief, and logged the amount to the millimeter. Memorable rain. A nurse stuck a thermometer into his mouth. As she waited for the beep and then entered the data into a tablet, she avoided his eyes. Lewis worried that he’d muttered something shameful while lost in the haze of anesthesia—that he’d told her he missed her, and loved her.

“Do you have grandchildren?” the surgeon asked.

Lewis nodded and raised his pointer finger.

The tall man, with bushy gray hair, wearing his white coat, set down the photograph Lewis wouldn’t take. “How old?”

He thought. “Seven.”

“They’re great.” The surgeon grinned. “Such joy.”

Lewis looked up at a basketball recap and read the teleprompter’s text: “The defensive prowess! Amazing!” He didn’t remember turning on the TV and decided he hadn’t. He wondered who’d thought that he would like ESPN.

"They love the pictures,” the surgeon said. “They’ll poke your stomach and ask if it was really in there. They’ll want to see the scar again, and make you scan the pictures so they can show it off at show-and-tell.”

“Thirty-two days.”

“I don’t imagine you’ll feel anything after a few weeks. You’ll be surprised how much better you’ll feel knowing this little guy’s gone.”

Lewis smiled and nodded because something like that was expected, but he was looking at the window now and wishing they hadn’t drawn the blinds. He wanted to watch the rain. Better if he could be out in it, unhooked, far from the hospital and all its clicking and beeping, far from the nurses and the fit surgeon so proud to have cut out some little troubled part of him.

***

In the middle of the night, the television was off. He couldn’t find a clock, but machines whirred and clicked. In his stomach he felt a dull ache, and later he didn’t. He watched the shadows on the wall or dreamt the shadows—a series of grain silos, as if he were a teen again, farming in central Oregon, changing irrigation pipes, driving a combine. He’d driven a combine, that huge machine. He’d used his hands. He tried to sit up with an idea of finding his phone so he could check the time. Maybe he’d check his work e-mail and see what was happening at the office. He couldn’t seem to move, though. He must have been asleep, dreaming, because nurses kept coming in and finding new veins, and hooking him to more IV bags. He was surrounded by the bags of water hanging from shiny white stands, and he felt the water dripping through the tubes and coursing through his veins. He could hear it.

***

The smell of the hospital followed Lewis into his Camry and now, as he put the car into reverse, seemed somehow to emanate out from a granola bar wrapper balled up in the cup holder. On his face he could still feel the phony smiles he’d given the discharging crew and the surgeon, who’d walked him to the elevator, clapped his back, and hoped that he, the surgeon, and his team had exceeded Lewis’ expectations—as if the surgeon himself, no autonomous master, was just another little part of the customer service machine that so diminished one’s dignity. Lewis was a project manager for an office solutions company and understood diminished dignity. He’d taken ten days of vacation time and told his colleagues that he was visiting family.

His windshield wipers squealed as they smeared the rain across the glass, and he felt certain the next day it would again register the minimum .01 inches of precipitation. It would be measurable. Maybe it would just keep raining. Though he wasn’t religious, Lewis liked the idea of a biblical flood—an immense cleansing, the chance to almost start over.

Inside his house, the central heating hummed, and he could smell the curious warm air that made him wonder if he needed new carpet. How had he forgotten to turn down the heat? On the answering machine, the number five pulsed in red. Lewis kept a landline, with the same number it had always been. He pressed Play, but all the voices were automated, the last message listing a string of numbers and letters he could use to redeem a 50-dollar voucher from the Toyota dealership, for service on his Camry.

Lewis played Mahler on the stereo. He liked Mahler the best and wanted to celebrate being away from the hospital. He wanted to celebrate the coming record, the persistence of the rain. He stretched out across the living room couch and looked out the window and must have fallen asleep because the doorbell startled him. On the other side of the glass door, a boy with a black eye and scabbed lips, his face gaunt and so pale Lewis thought at first it was another dream, clutched the handles of an orange Tupperware tub. On the street, the boy’s mother, bundled in a blue winter coat, held an umbrella in one hand, a cigarette in the other. Lewis opened the door and looked past the boy, and maybe even smiled as he waved at this stranger, who didn’t wave back. His effusive wave he would later blame on having been asleep, and medicated.

“I’m selling candy,” the boy said. He wore a gray hooded sweatshirt and oversized blue jeans, darkened by the rain. He set down the tub and held a laminated card. Not once looking up, he read: "Hello. I’m Todd. I’m selling candy for the Joe Thompson Boys Club. It’s an organization that helps keep at-risk boys off the street. Would you like to buy some of this candy? If you don’t want the candy, would like to make a donation?"

The mother drew the cigarette to her lips, looking off down the street, surely wishing she was somewhere warmer, dryer. Lewis didn’t want any candy, years old he figured, not that time mattered much anymore with food, but he looked again at the woman and told the boy to wait. He couldn’t find his wallet, and when he did he only had two twenties. Upstairs, in his bedroom closet, he smelled the cedar, which he replenished every few months, and the leather of his dress shoes, and he inhaled and held in his breath as he dug out the box of cash he kept in case the power grid failed or the big earthquake hit. He found a five.

But the boy and the mother were on the street, walking away from the house. Lewis wondered how long he’d been searching for the money—it couldn’t have been more than a few minutes.

“Hey!” he yelled.

The woman looked back. She raised an arm and flipped open her hand as if it were a flower blooming, which must have been some obscene gesture.

***

Lewis woke up on his bed, atop his comforter, dressed. He touched his pants, his scratchy wool sweater. He heard the rain—and something else. Was someone really down at the front door, knocking? The clock radio on his nightstand read 2:14, but he didn’t believe he’d been asleep. He tapped the clock. Nothing. Then it changed to 2:15. He heard the knocking again and tried to get up, but he felt as if something had torn open in his stomach—and it was impossible that someone was visiting.

***

In the morning, more rain fell. “A record,” Lewis said. He didn’t like when he spoke aloud but sometimes words escaped. He could even find himself singing, in a soft goofy voice, ridiculous jingles he’d compose after annoying days at work: “Oh yes! We’ll meet all your diverse copying needs—you’ll see!—we’ll collate and staple and fill you with glee!” In the family room, he switched on the TV and when they got to the weather, the meteorologist was wearing a green party hat. He blew a party horn. “We have a new record,” the man said. “Thirty-four consecutive days of measurable rain!”

The anchor man, smiling, shaking his head: “A dubious feat indeed.”

“But remarkable, even for Seattle!”

“I can’t imagine they’re celebrating in Centralia.”

There was flooding in Centralia.

Lewis switched off the TV. They were making a joke of it. They made a joke of everything. Beyond the windows rain dripped from a plastic bird feeder he’d hung years earlier from the large maple, which he still kept full of seeds. The plants, mostly ferns, leaned under the weight of so much water. He swallowed another painkiller and wondered if the surgeon, that confident prick, had screwed up.

Outside, uncovered on the patio, he stood on pavers green with moss, and felt the rain in his hair. He still had a full head of hair, graying in places, but not visibly receding. The meteorologist must have smiled as he crouched to read a more accurate measurement, amazed. Lewis imagined the man entering the data into a tablet, which synced with more powerful computers. He sat on a paver, stretched out his legs, felt the cold water seep through his pants, felt the cold cement and little stones on his palms, and pictured a room full of computer screens, meteorologists with their charts and graphs and all their data, which would provide patterns, predictions, explanations.

***

It rained the next day and then the day after that. Then the rain stopped. And the following morning, on the radio, the voice reported that the string of consecutive days of measurable rain had been broken. “Take a deep breath, everyone,” the voice said. “Savor this. The remarkable streak is over.”

***

Lewis woke up on the living room floor wearing a pair of navy-blue sweat pants he didn’t remember owning and a gray sweatshirt his daughter had worn when she’d come back from college, complaining of how cold and wet it was now that she lived in Arizona. She’d stayed in the desert and to Lewis’ knowledge no longer came home. It was terrible that he’d put it on, yet he couldn’t remember digging it out. Although he walked in his sleep two or three times a year, waking curled up in different parts of the house, Lewis couldn’t recall ever changing clothes while he slept. He hurried upstairs and bathed himself. He put on a pair of khakis, a button-down, and a gray sweater. Outside, it was still so wet, and water dripped from the eaves, but it didn’t rain. It was cloudy, but the clouds were spent.

***

His stomach ached. Lewis slipped his pinky finger under the gauze and touched his stitches, prickly, and knew that he needed to return to the hospital and explain that something had gone wrong. A stitch inside him had come loose. Yet when the nurse called again to check on him, Lewis assured her that he was doing well. He drove to the supermarket. In the cereal aisle, he encountered her. She was staring the other way, at the coffee. She had on the same blue jacket, and he could see that she was younger than she looked, maybe in her late-twenties, about the age of his daughter. But she wasn’t well—her skin, like her son’s, so pale, her hands so bony. A drug addict, probably, or maybe she had cancer, something that couldn’t be cut out, something malignant.

Lewis grabbed a bag of coffee and pretended to read the description. He didn’t drink coffee. “The streak’s over,” he said, and wished he hadn’t. How many times had she heard that bit of banal small talk since the rain had ended?

“Hardly,” she said. “Where I live.” She clutched her green basket. In it were packages of Ramen noodles and a box of Minute Rice and sliced bread and grape jelly.

“Did your son sell enough candy?”

She reached for a container of Folgers.

“I was trying to find my wallet,” Lewis explained, “to give a donation.”

“Will you pay for this?”

He paid for her groceries. The cashier, heavyset, her hair permed, seemed suspicious and wouldn’t smile as she handed him the receipt. She didn’t thank him or wish him a good day, and she glared at the woman, who’d stuffed her hands into her pockets. Maybe he needed to find the manager and file a complaint of bad service. He’d stand up for her, for them. Lewis smiled at the absurd thought and yet noticed that he was standing taller as he followed her out the automatic door.

In the damp gray of outside, she touched with two fingers the red plastic box of the Pennysaver advertisements. “Can you drive me to my apartment?”

***

In the Camry, he kept glancing at her hands. Nicotine stained her fingertips, and he wanted to smell them. He wanted to hold her hand to his face and fill his lungs. He’d smoked once, for a month when he was 22 and backpacking through Europe, and he’d enjoyed the scent that lingered on his fingers. She stuffed her hands into her jacket pockets, shook her head, and frowned, and told him to turn right.

The apartment complex was massive, a cinderblock edifice, five stories, built into a hill. It’d been a motel once—The Grand—and had opened to some fanfare but soon failed. The rooms had been converted into apartments. Lewis watched as she fumbled with her keys and finally got open the glass door. Then she appeared on the second floor and crossed the open walkway. She stopped at the last door and set down the grocery bags before opening it, but when she grabbed them again she didn’t look back to see him waiting, clutching the wheel with both hands, craning his neck so he could see.

***

Over the phone, as he stood in the living room watching the gray, rainless sky, he filled a prescription. He heard the surgeon: Can’t imagine you’ll need this one. An automated voice asked if he needed expedited service. Lewis spoke to his phone: “Yes.”

***

He coughed up blood. In the bathroom, he was 18 again, clutching the toilet, his first time drunk. Remarkable—how quickly it all unraveled. How awfully. When he finished, Lewis wiped off the sweat and spit and blood with a warm damp washcloth and rinsed out the iron taste with Listerine. In the pharmacy parking lot, he dry-swallowed the painkiller, and later he reached her apartment complex. And then he stood at the entrance, amazed, impressed that he actually stood there looking at a wall of mailboxes through the glass door. Against the initial wave of the painkiller, warm and heavy, he felt a nervous thrill.

The call box rang four times before she answered.

“Hello,” he said. “I gave you a ride home two days ago.” He added: “I’m outside.”

In the static that followed, Lewis assumed that she’d hung up—the most reasonable course of action. People moved to these places to hide. His own daughter had moved to Arizona to hide—and you had to honor that, you had to accept it. I’m staying here. Fuck all this gloom. She’d stopped writing after that, stopped responding to his email, and stopped visiting. He needed to leave, return to his house. He’d make it back to work on schedule, and if they asked him what was wrong he’d say he was just battling a little stomach bug, that’s all. It was a great trip otherwise. The family was good, yes. I’m doing well. That’s what he always told them when they asked—I’m doing well.

The door was buzzing.

***

She sat on a futon mattress watching TV. A tangled-up brown blanket, a flannel blanket like one he had at his own house, touched her hand. A tiny TV set was on the floor, its cord hazardously stretched to reach a socket, and Judge Judy or some other judge—he rarely watched TV—thrust out her pointer finger at a man and said something Lewis missed.

The room was smaller than his bedroom. At the far end, he could see what must have been a tiny kitchen, and straight ahead was a hallway with two doors, both closed. The walls were brick, painted bright white, too bright, and they were empty of any art work. Pushed against one wall were a table and two chairs, out of proportion, the table too high for the chairs. The ceiling, he noticed, was a weird yellowish color, speckled with mildew. It glistened, though, with drops already formed near the middle.

“Close the door.”

She’d combed back her wet hair. She wore faded blue jeans, gray socks, and a waffled, long-sleeve shirt. She motioned, jerking her head inward, annoyed, it seemed, that he just stood in the doorway.

Lewis entered. He even closed the door, he noticed, and as he stepped to avoid the mattress, he smelled shower and cigarette and something else, earthy, a place he’d visited perhaps, camped at when they were still a family, in Idaho, or Montana, a musty tent. He couldn’t get back far enough to know exactly where that smell was from, what memory, and if it’d been with his wife and their daughter—and then he felt something different, a strange urge to smoke. He watched his feet, his brown boat shoes, his favorite, a step, and another step. At the table, too tall to be a proper dinner table, too tall for its chairs, he sat. A Hispanic woman at a lectern, full of wild outrage, cried, “He took my schnauzer! I had Sheila since she was a bitty puppy. I nursed her with a little bottle once even!”

"Judge’ll rule against her,” she said. She shook her head. “Doesn’t matter if you’re not guilty. Judge can’t stand those emotions. She once told a guy whose ex-wife, without a doubt, emptied sacks of rotten meat into his car when he was out of town, and ruined it, ‘You have a lot to learn about dignity, about just being quiet.’ She ruled against him.”

"Do they enforce the rulings?”

“That’s not the point.”

“What’s the point?”

“It’s just being quiet. That bailiff there.” The stout man, with a fake tan and a bald head, stood unmoving. “That’s the point. How he stands there, just like that—through it all—even right after he breaks up a fight and walks back into the courtroom.”

“There’s nothing about renewal?”

She snorted, twisted her face, almost twitching, it seemed—what a joke—and batted her hand as if through the TV and right into the show. “Like they got some special shower back there, the magic shower? You think there’s a magic shower that’ll fix you up?”

He watched a commercial for a home security system. A burglar crept into a house, terrified a child, stuffed handfuls of jewelry into a pillow case. Lewis noticed more drops were forming. He counted fourteen drops.

“You’re sick too.”

Her words seemed to float about the room before Lewis registered them. “They’re expecting me back at work,” he said, “on Monday.” His ring finger followed something carved into the table: an F. “Forever.” “Tammy + Brian Forever.” Someone had carved “Slayer,” someone else an erection. Most of it was indecipherable, though, carvings over carvings, characters, it seemed, of a far-off language.

The judge ruled against the Hispanic woman, who howled.

“See.”

“Where’s your son?”

She frowned—and Lewis realized that nothing in the room suggested a teenage boy or any kind of family. She pointed at the fat drops on the ceiling. “It’ll start soon.”

"That day you stopped at my house,” Lewis said, “when I waved, and your son was selling candy—that night—late that night—the morning, really.”

“Watch.”

A drop landed on the carpet. He saw it fall, the first drop, and right after it hit, the TV was louder, another commercial, local, low budget, for a team of personal injury lawyers boasting of their aggressive nature. One of the lawyers, so smug and confident, his hair slicked back, clutched a baseball bat. A prick, all pricks. His surgeon. Then silence. She’d pressed Mute. She set down the remote and without even a glance to explain any of it crawled, clutching the blanket, under the table, disappearing completely from his sight. The blanket disappeared. Lewis looked at the table top, his fingers pressed into the grooves where so many kids had tried to leave behind some lasting trace.

A drop hit his thigh and spread to the size of a dime. Lewis touched it, and then he touched his stomach. Even with the painkillers, the ache persisted, and on the TV, still muted, each mouth moved more frantically, more anxiously than the last. A man at the lectern pointed at a woman, who pulled back her shoulders, cocked her head, and glared. The judge wagged her finger at them both, and her mouth twisted up in some rebuke. The judge was probably right—he needed to flee her awful little apartment and drive straight to the hospital and find out what had gone wrong. But Lewis didn’t want to leave. He didn’t want to face the surgeon again. He didn’t want to go to work. He wondered how many days in this apartment it had rained consecutively. Months, perhaps. Every day. They wouldn’t mock this rain, this record. A drop hit the TV. A drop hit Lewis’ head, and he looked up at the moldy ceiling dappled with so many new drops. He understood that she was right to seek cover. There was no special shower. And yet when he slipped off the chair and knelt down on the carpet, she was there, sitting cross legged with the blanket around her shoulders, like his daughter, looking out as if from a bluff, as if surveying new land, trying to decide where to settle. She had come to his house. It had to have been her, this pioneer. In the middle of the night, she’d returned to his house and had knocked, for whatever reason, the money, probably—but at least return was possible, he hoped. Lewis climbed under the table and turned around to face the room. A drop fell, but he was safe now.

“Every day this happens?”

“Summer it can clear up, if you’re careful. If you keep the door cracked open.”

“Is it measurable?”

“How are you going to measure?”

“At the airport,” he said before he could stop himself, “ they measure the faintest traces of rain.” At work, he compiled reports, pages amassing so much data, which explained everything, which made sense. In meetings, he could deliver these reports with such confidence.

“That’s stupid,” she said.

And then she motioned toward the TV. “There was a guy on once. His neighbor sued him because the guy, late at night with some kind of plant killer, wrote a message into his front lawn. He did it with big capital letters, a letter or two a day, so it appeared bit by bit as the grass died: ‘TOXIC DEATH SHAWL.’ We all saw the pictures the plaintiff took, from about every angle possible. The words were two feet tall. Otherwise, it was one of those perfect lawns from the commercials. He must have taken a hundred pictures, probably filled up his phone with pictures.”

As drops pattered on the carpet, she reached out from under the table for her cigarettes and the ashtray, and her bony fingers fumbled with the bent pack. She drew the cigarette to her lips and lit it.

“What’d it mean?”

“That’s what the plaintiff wanted to know. Judge even wanted to know, I think, but she was way more annoyed with the plaintiff for being such a whiny shit, for thinking he could get some answer, and threatening to beat the defendant up, calling him ‘weirdo scum, with a crappy yard.’ ‘No one likes you.’ ‘Smug little neighbor.’ But the guy wouldn’t budge. His name was Cyrus something, I remember. He was calm, like he was on a tranquilizer. He had on a green tie and he’d just sort of wave his hand like he meant everything, all of it.”

“All of what?” Lewis watched a man at the lectern pinch his upper lip.

“Everything. That kind of neighbor, probably, with a lawn like that. A guy who’d take that many pictures.”

“She ruled against Cyrus?”

“No.”

***

“Can I have one?” Lewis asked.

She set the cigarettes near his knee and handed him the lighter. He hoped she wasn’t watching as he extracted one, straightened it, and, holding it between his thumb and pointer finger, brought it to his lips. The lighter caught on the first try, and the cigarette crackled as Lewis inhaled.

“You don’t smoke much.”

“I did,” Lewis said. His brain tingled. He felt embarrassed, a kid. But then he inhaled and didn’t cough and was in Berlin, smoking, staring at the enormous wall where people had spray-painted so many protest slogans. On the other side, the barbwire, which would snag people and hold them while they got shot. Lewis had been unable to imagine the courage it would take to try to cross over. He couldn’t comprehend the kind of despair, or love, that would propel someone to scramble into such a mess.

The woman cleared her throat, and Lewis was back under the table, and a new pain flared in his stomach. Somewhere a drop hit a sheet of paper and it sounded as if someone knocked. Maybe he startled.

“It’s louder than you think,” she said.

“Did you come back?” Lewis asked. “That night after the boy had tried to sell me candy. I heard someone knocking—in the middle of the night.”

With her free hand, she brushed the idea away. “You need to be quiet,” she said, staring straight ahead. She seemed to have forgotten about the end of her cigarette, smoldering, sticking out from her fist. “You’re the one ended up here. You’re the one thinks there’s renewal in all this. You need to listen.”

Lewis did. He listened. Pain radiated out from his stomach, and the smoke kept building around him. As he looked out, the room seemed to spread much wider now, expanding with each new drop. It made him dizzy, how much it seemed to expand—all this new, terrible space—until he had to close his eyes. The drops still fell, though, and each drop sounded louder than the one before, louder than any rain he’d ever heard.

Copyright © June 2021 Steinur Bell